This is the architect who designed PS5, PS4 and PS Vita, and who helped birth characters like Crash and Spyro. One of the great talents of the video game industry.

"Mark Cerny is the closest thing to Da Vinci that we have today." With these statements (before which it is difficult not to sketch a grimace) began the speech that, in 2010, welcomed Cerny in the Hall of Fame of the Academy of Arts and Interactive Sciences (AIAS). A recognition within the reach of very few that served to claim one of the greatest talents in this industry. Unfortunately, many people today only associate Cerny's name with his latest game, the more than questionable Knack, and the sobering first presentation of PlayStation 5, but nothing is further from reality. His list of contributions to the sector dates back to the 1980s and encompasses feats such as entering Atari when he was still a minor, saving Sonic from disappearance, helping to create the characters of Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon, making Sony completely change your work philosophy, and be the architect behind PS5, PS4 and PS Vita, among many other merits. Today at FreeGameTips we have set out to delve into Cerny's career and review her endless history, or what is the same, to know a little better about one of the people who will give us the most joy in the coming months with the arrival of the new generation. We are, as the speech continued, before a true man of the Renaissance.

“What he does is not restricted to one aspect of video game creation, he really is a man of the Renaissance. Accumulate achievements as designer, producer, programmer and technology manager. He is fluent in Japanese and has become one of the greatest western experts on the Japanese market. In addition, he is one of the few top entrepreneurs to remain independent in a business dominated by large institutions and corporations. His contributions to different projects have been tremendously successful, with more than two billion dollars generated and a dozen titles that have exceeded two million units. It has left an indelible mark on all the games it has been a part of and has redefined how the industry thinks in matters of design, technology and production philosophy ”. Will you live up to these words?

Another genius who skipped college

Mark Evan Cerny was born in 1964 in Burbank, United States, a small California city that he would leave with his parents in a few years to go live in San Francisco Bay, not far from there. The journey between both cities crosses places like Palo Alto and Silicon Valley, both the cradle of technology. Who knows, maybe he was predestined to be one of her prodigal children. Also in the area is the University of Berkeley, where he began his studies. However, just like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg and Daniel Ek (the founders of Microsoft, Apple, Facebook and Spotify, respectively) did, and following in the footsteps of many other geniuses, Cerny was quick to drop out of the race, in his case to work in the ranks of Atari, which he had joined in 1982, with only 17 years old. There he put his talent at the service of many projects, but he did not make a name until he designed and programmed his first success: Marble Madness, a classic of the 1984 arcade games.

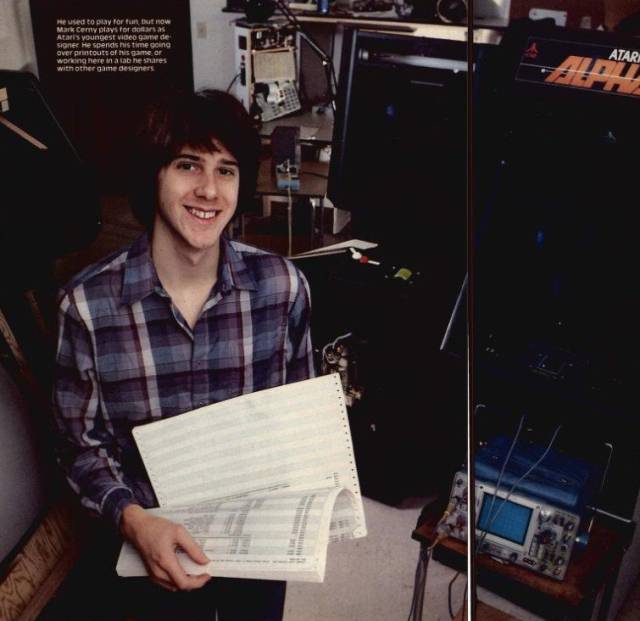

Mark Cerny in 1982, at age 17, when he joined Atari.

Mark Cerny in 1982, at age 17, when he joined Atari.

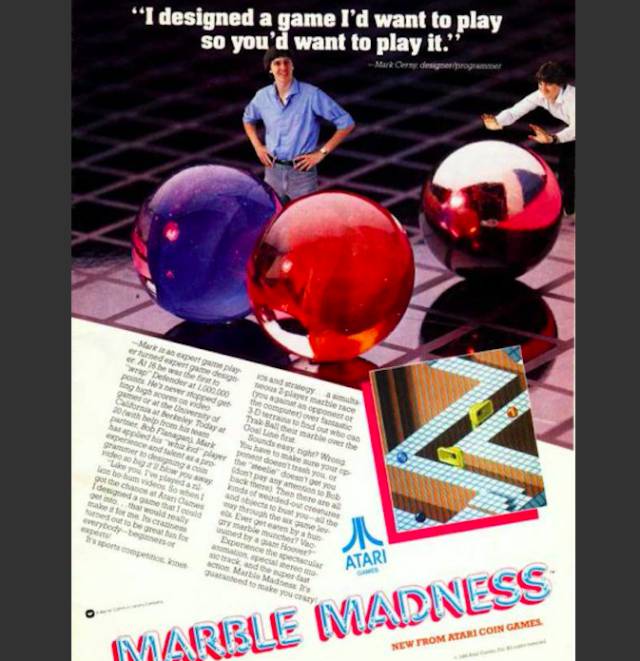

Mark Cerny's first game: this was Marble Madness

Marble Madness was a platform game in which we guided a marble through different scenarios full of obstacles and enemies, which we had to overcome within a limited time. It had such a good catch that it was adapted to most of the third and fourth generation consoles, and years later, in 1991, until a sequel was developed in which Cerny (Marble Madness II) no longer collaborated, which later even it would follow a reboot in 2002, Marble Blast, with its respective continuation, Marble Blast Ultra (2006). Despite its apparent simplicity, the title laid the foundations for a genre from which classics such as Katamary Damacy (2004) and Super Monkey Ball (2005) would emerge, and which has had dozens of heirs over time. There they are, for example: Kula World (1998), RocketBowl (2004), Kokorinpa (2006), Switchball (2007), Spectraball (2008), Rock of Ages (2011) and inFlux (2013), among many others.

This is how Cerny himself spoke for the Sega Retro magazine about this first project: “It was an incredible time to make games. Especially since the teams were very small and the games used to be made by one person, so we were all a mix of programmers / designers and we also did our own artwork. In Marble Madness, apart from me, there was only one other programmer and an artist. ”

In any case, Cerny didn't just focus on making games during her time at Atari. As if the Moiras already knew of his destiny, there he was awakened by his curiosity about the world of hardware, in which he designed and built several arcade boards. Developing hardware in 1985 was very different from how it is today. I designed something for arcades on my own, but because then you could go, buy a handful of chips and put them on a board. Today we are talking about large transistors and compiled chips. You're not in a position to do something like that. In 1985 there was almost no difference between someone amateur and a professional, ”he declared in 2013 to Develop magazine.

1984 advertising article on Marble Madness, Mark Cerny's first hit game. "I have designed the game that I would like to play so that you want to play it."

1984 advertising article on Marble Madness, Mark Cerny's first hit game. "I have designed the game that I would like to play so that you want to play it."

Knocking on SEGA's doors

"The important thing is not to arrive, but to stay." Who has not heard of authors who have been forgotten (and even disappeared) after having their first great success? In 1984, after Marble Madness, Mark Cerny decided to leave Atari and go on his own. "I thought that if the teams were already owned by one person, what was preventing me from being the seller too?" He confessed at the time. "I made some contacts and convinced them to finance my next project." Arrogance and adolescence have always gone hand in hand (remember that I was only 19 at the time) and very soon discovered that things were not so easy. "I collided with reality. Development was slower than expected and a year after starting I had made little progress. ” Without the financial cushion of a company behind, Mark Cerny's career could have ended there, if it had not been for one of the contacts he had made was that of Hayao Nakayama, president of Sega since 1983 and main architect of the company entering the domestic console market. “Nakayama suggested that I abandon the project and go to Tokyo to work for him and what would soon be his new console, Master System. I said yes and basically I got on the first plane that left for Japan. "

Michael Jackson visits JP Sega 12/16/88, dev room w Mark Cerny, rides Power Drift, gets Galaxy Force 2 as a present!

(HQ pic Insert Credit) pic.twitter.com/NUu8VItiZy– Chris Covell (@covell_chris) April 17, 2017

Why did a company in crisis trust a 20-year-old boy?

To understand Sega's offer, one must understand, in addition to the tremendous success of Marble Madness, which we have already explained, the situation of the company and Nakayama himself back in 1985. Although Sega had reigned in the field of arcade machines, the success of these began to decline in the early eighties and forced the company to restructure completely. It was the first crisis in the video game, with the Atari debacle involved, and ended with the Sega itself being sold to a US company, Gulf and Western Industries, of which Hayao Nakayama was a part, who convinced his superiors of this purchase. Among those superiors was David Rosen, who later Nakayama would also convince to sell the rest of the company to stay only with Sega. Both believed that the future of this would come from entering to compete in the market for home consoles, just as Nintendo did at the time with its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), which came out in 1983 and became the first platform to overcome the crisis. In other words, Nakayama, still of Japanese origin, was an entrepreneur who came from the United States and knew the situation (and potential) of video games globally very well. Between 1979 and 1983, he went from being a mere distributor at Gulf and Western Industries to president of Sega Enterprises. The amount and importance of the decisions he made in those days made him a brilliant mind that was well worth his own article.

But why did Nakayama decide to fish among American developers for Master System? This was explained very well by Cerny himself in the interview with Sega Retro: “In Japan the arcades were still successful and Sega created a couple of must have every year, but outside things worked very poorly. During the following years I think there was a time when NES accounted for 94% of the American market and Master System had only 4%. Nintendo was 24 times bigger than Sega abroad! ” Nakayama tried to globalize the company and for this he attracted some of the thinking heads behind the successes that he had known in the United States. Mark Cerny was one of them. However, the results were slow to arrive. Quoting Cerny again: "In 1989, when Mega Drive arrived, Sega was an organization that had gone to war with Nintendo and had basically been wiped out." The consequences of the arrival of foreign talent were slow to be seen and between 1985 and 1991, although Cerny collaborated in many games, he never found the key. To save Sega, Cerny first had to save Sonic.

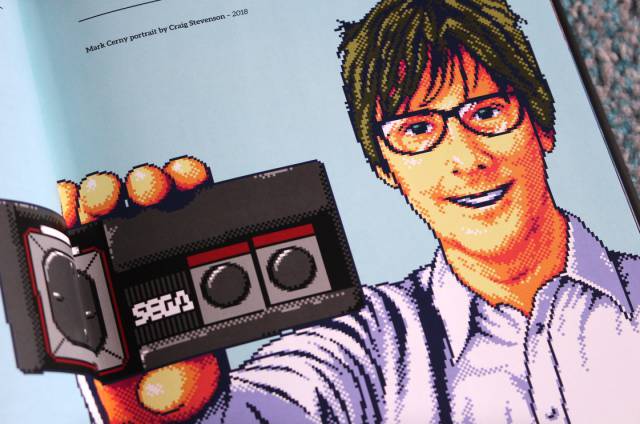

Portrait of Mark Cerny with a Master System controller for the book 'SEGA Master System: A visual compendium' (2019).

Portrait of Mark Cerny with a Master System controller for the book 'SEGA Master System: A visual compendium' (2019).

The American who saved Sonic

The stage in Japan will surely be key to understanding the whole future of Mark Cerny. There he learned Japanese, met his future wife, and worked on games like Shooting Gallery (1987) and Missile Defense 3D (1987). "It was a culture shock," recalled the developer. “There were about forty people in a single room and they were trying, in this single room, to create all the possible games for the launch of Master System. Projects used to have one or two programmers and lasted a maximum of three months. The pressure was very, very high. But we did a great job and there were some very talented people, like Reiko Kodama (designer of Phantasy Star), Yuji Naka (director of Sonic) and Yu Suzuki (creator of Virtua Fighter and Shenmue). ” (If you want to read more about this era and the rivalry with Nintendo, we highly recommend the article 'Sega: Rise and Fall'). In 1991 Cerny was ready to go on his own again, and since he had earned Sega's respect and trust, Nakayama proposed that he lead his "expansion project in the United States." This is how he returned to his country and became one of the standard bearers of the Sega Technical Institute, the branch that made possible jewels such as Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (1992) and Kid Chameleon (1992).

During his stay in Sega he made good friends with creators of the stature of Yu Suzuki (the one that appears above the separator on the left). Here, they both show Steven Spielberg and his son a demo of Virtua Fighter.

During his stay in Sega he made good friends with creators of the stature of Yu Suzuki (the one that appears above the separator on the left). Here, they both show Steven Spielberg and his son a demo of Virtua Fighter.

After the first Sonic, the hedgehog's creator and director, Yuji Naka, and his main level designer, Hirokazu Yasuhara (whom Cerny would later turn to for Jak & Daxter's conception), left Sega due to various disagreements with the company policies. "His departure left me in shock, so I found out where Naka lived and I fell," Cerny would admit later. “I remember living in a rather dingy building, but he said it was perfect because it was only a few minutes from the office. In any case, I listened to the problems I was having and started thinking about how to solve them. And, of course, the financial issue was one of them. " Cerny offered them a higher salary and more creative freedom, so they both accepted and were part of one of the first multi-national teams in the United States. STI's plan was to bring together some of the best minds in the Japanese industry to mentor young American developers without much experience. Cerny wanted to unite their working philosophies and bring out the best in both countries. "We explained to Nakayama that when you are in Rome you must do what the Romans … and he left us full autonomy." Although Yuji Naka was reluctant due to cultural and linguistic barriers, the pieces of the team ended up fitting in and years later the director would end up telling many of the stories and complications that arose during development, but he would also admit that they had been good times. As a result and against all odds, the Sega Tecnhical Institute gave birth to the legendary and outstanding sequel to Sonic (and later, although without Cerny, also to Sonic the Hedgehog 3 and Sonic & Knuckles). Who knows what would have become of the character without that surprise visit and without the direct intervention of Cerny.

Photo of Mark Cerny eating with the Japanese members of the Sega Technical Institute, where Sonic the Hedgehog 2 was made. To his right, Shinobu Toyoda (vice president of Sega in America).

Photo of Mark Cerny eating with the Japanese members of the Sega Technical Institute, where Sonic the Hedgehog 2 was made. To his right, Shinobu Toyoda (vice president of Sega in America).

Your first contact with Sony and PlayStation

The thirties were just around the corner, but Cerny was still hungry for challenges, so he left the Sega Technical Institute and joined Crystal Dynamics to test and experiment with three dimensions and 32 bits. The STI would close just a few years later, in 1996 (here you can read about the complex reasons that led to it), and the rest is history (very well narrated also in articles like 'Where Sonic Went Wron'g, by Game Informer). Already in his new house, our protagonist collaborated in games such as Crash 'n' Burn (1993) and Total Eclipse (1994), although if he attracted attention for something it was to close his first agreement with Sony. Cerny made Crystal Dynamics the first company outside of Japan to get one of the first PlayStation development kits. For this, he had to negotiate in person with a very young Shuhei Yoshida, then product manager of the Japanese giant. Sony had been refusing to ship its hardware outside of Japan, but Cerny, who did not take no for an answer, stood at its headquarters and made a great first impression thanks to the fluency of its Japanese, the great obstacle that the other companies when making themselves understood and signing contracts. Although the prices of the developments were rising, the advantage of the dev kits made Crystal Dynamics invest fearlessly “between two and three million for each PlayStation game”, certain that it was going to achieve remarkable financial results (as it was). It was the time when he gave us works such as Gex: Enter the Gecko (one of the brand's first pets back in 1998 and his response to Mario 64), or the legendary Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver (from 1999).

Interestingly, Mark Cerny would never get to try those development kits, because shortly after signing the agreement and already in 1994, Universal Studios, the all-powerful conglomerate dedicated to music, cinema and entertainment in general, made him an offer that did not He could let go: be vice president of his new video game section: Universal Interactive Studios. But Cerny's ties and ties to Sony's platforms were only going to grow.

Mark Cerny and Amy Henning (director and screenwriter of Uncharted, Legacy of Kain and Jak 3) met during his visit to Crystal Dynamics, where they both met back in 1993.

Mark Cerny and Amy Henning (director and screenwriter of Uncharted, Legacy of Kain and Jak 3) met during his visit to Crystal Dynamics, where they both met back in 1993.

The person who discovered Naughty Dog and Insomniac Games

Cerny spent four years as Vice President of Universal Interactive (from 1995 to 1999), in which he was able to do and undo as he wanted, as he recognized in a talk during a 2013 Develop Conference Keynote in Brighton, England (you can see it under this paragraph. ). "Universal did not know the sector and as a result, I used to have a large bag of money to invest and no supervision." Of course, I wish we all had his intuition. With such financial support, the designer hired a company of just three people called Naughty Dog and a two-member start-up named Insomniac Games. Does anyone sound like something? Both are today two of the cornerstones of PlayStation Studios. The first since 2001, when its agreement with Universal ended, and the last after being acquired for more than $ 200 million in 2019. During Cerny's tenure at Universal, both companies created the characters of Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon, whose Early video games have eventually sold a whopping more than 20 million units between the two. It would be the beginning of the endless number of characters that the two studios would make for Sony and that would inevitably be associated with their brand: Jak & Daxter; Ratchet & Clank; Nathan Drake of Uncharted; the Resistance chimeras; Ellie and Joel, from The Last of Us; Spider-Man … etcetera.

The day Crash Bandicoot made him cry

Although it seems that everything was rolled, far from it. The book All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How 50 Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture collects a famous anecdote that tells how Ken Kutaragi, the father of PlayStation, threw a 45-minute fight at Cerny that left him on the verge of tears . All because, amidst the stress and bustle of E3 in 1996, Kutaragi saw no future for Crash Bandicoot just before its presentation, and considered that it did not live up to what they wanted to show. "Ken is a very intense person," says Cerny in the book. It would not be her last disagreement with him, as we will see later. In any case, Cerny always had to live with doubts and false prophecies about her work and her decisions. At Sega, when asked about the character design of the first Sonic, Cerny showed several prototypes to the marketing team that the company had in America and there they assured that the prototypes were "a complete disaster" and that they were "insurmountable". Fortunately Cerny ignored them, supported the originals and Sonic and his universe ended with the aspect that we remember today.

And despite everything, Cerny's privileged position began to falter, and although he was one of the best-considered and highest-paid executives in the industry, in 1999 he had to face the serious economic problems that suddenly plagued the video game section of Universal and that would end in 2000 with its sale to Vivendi. The company lost contracts with Naughty Dog and Insomniac, who started making games for Sony on their own, and Cerny had to make one of the most difficult decisions of his life. “I had to choose between staying with Universal as president and trying to make things work, or becoming independent and working as a consultant for developers like Naughty Dog, Insomniac or Sony, studios that I really loved. Of course, I chose the second one. ” This is how Cerny Games was born, a company co-founded with his wife that was established in 1999 and had the first mission to help the creators of Crash and Spyro make the leap to PlayStation 2.

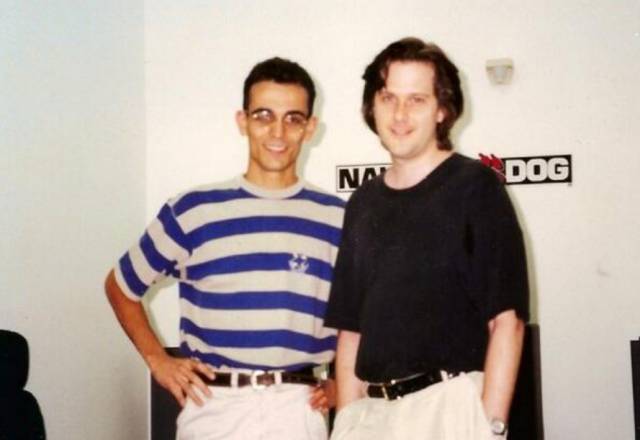

Mark Cerny in the late '90s, when he discovered Naughty Dog and Insomniac Games and started working with them on Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon.

Mark Cerny in the late '90s, when he discovered Naughty Dog and Insomniac Games and started working with them on Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon.

Sony, the only company that Cerny has not abandoned

Let's review so far. We are in the year 2000, Mark is 36 years old and has already left Atari, Sega, Crystal Dynamics and Universal, almost nothing. It is as if I had wanted to be independent since Marble Madness, back in 1984, when that famous question was asked: what prevents me from being the seller too? The only company in his career that Cerny has worked for and has never resigned from is, oddly, Sony, but basically because he never became a part of it. Despite the strong relationship that will strengthen and establish from here, Cerny has always been an external consultant in all the charts, including being the architect behind PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita and, in brief, PS5. A contractual relationship like no other has been seen in the industry, a rare bird that has been carefully studied in articles such as 'Sony's Most Valuable Contractor' and 'Cerny Computer Entertainment'. He has always remained the director of Cerny Games, an independent entity from Sony that has no major responsibilities within it.

Mark Cerny in 1999, when he was already president of Universal Interactive Studios, during a video interview for PlayStation Underground.

Mark Cerny in 1999, when he was already president of Universal Interactive Studios, during a video interview for PlayStation Underground.

"I can contribute freely and without having problems with the limits of the organization … because I do not belong to it," Cerny explained more than once. He occupies a unique position in the chain of command of Sony that allows him to pursue his interests and help in different projects avoiding any type of bureaucratic blockade. Officially, he has no responsibilities and refuses, for example, to devote himself to the field of hardware full time. In fact, he continues to dedicate half of his time to video game development. “When a project ends nobody says: hell, what do we do with Mark now? I talk to people myself and see if they can use some of what I know within Sony Worldwide Studios. ” This is how he has been jumping from one project to another (the last ones he collaborated on were The Last Guardian and Death Stranding)

His great thorn

Despite that very special position, Cerny has always wondered what would have happened if he had focused his attention on a single game. What would you have achieved if you had led a project and not thought of anything else from start to finish. "I would love to do that before I retire. But there aren't many in a position to do what I do either. ” With Knack, the last of which he was director, he had to combine his work with the development of PlayStation 4 and was forced to release the game ahead of schedule to launch it. The result took its toll on his reputation and, far from taking this situation into account, Cerny has suffered in recent years the persecution of dozens of memes related to her new character. Removing that thorn seems one of your goals for the future.

Cerny Games original logo (1999). For Cerny it was always very important to be independent. Dropped Atari, Sega, Crystal Dynamics and Universal.

Cerny Games original logo (1999). For Cerny it was always very important to be independent. Dropped Atari, Sega, Crystal Dynamics and Universal.

Your contribution to PlayStation 2

Going back to 2000 and the founding of Cerny Games, the company's first mission consisted of a new trip to Japan, which was established as its second home. There Cerny spent three months during the conception of PlayStation 2, becoming the first American to lay hands on him thanks to the relationship and trust he already had with Shuhei Yoshida, who even allowed him to participate in the creation of a first graphics engine for the console. . In this way, Cerny would collaborate with the team of programmers who, in the most absolute secrets, developed several demos for the platform before its official presentation, thus obtaining the necessary knowledge to later help Naughty Dog and Insomniac. With them he would later collaborate in programming and design work for the titles with which both would be released on PS2: Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy (2001) and Ratchet & Clank (2002), respectively.

The Cerny method

During those years, Cerny took advantage of the string of successes that already accumulated behind him and began to give several conferences on his way of working. The most important of them is still on YouTube and shows us a very young (and also very nervous) developer who talks about something known as "The method". Today some of his concepts sound obvious, but only because, as people from Ben Cousins' experience have stated, “they were practically advice that everyone implemented in this business. It's been a huge influence and a lot of people from outside the industry don't know that. " The Cerny Method gathers things like getting started by creating just a part of the game to show players what the experience will be like. "It is not that revolutionary," Cerny has acknowledged more than once. “The part we choose has to be representative. Once it's done, you have to look for feedback from the players and use it to turn the idea around and expand it until you have a complete game ”. In the same way, and as if it were a police interrogation, Cerny admits that he took people from the street and put them in his study, where he played them while he watched everything from the other side of a glass. "I wasn't talking to the players. He just paid close attention to their reactions and how they played. I was calling the team right away to make changes based on what I was seeing, ”recalls Andrew House, former president of Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Where do 80% of the errors in a video game come from?

Throughout his explanation, which is well worth a look, Cerny distinguished, for example, between pre-production and production. "They are as different as night and day." In one you have to try to capture "the light, the talent, the idea." Creative freedom must be taken and risks must be taken. In the second it is time to build the game. By the time the first one ends, the studio has to have that playable demo that will determine if the project will live or not. “Pre-production has to allow itself to be somewhat chaotic. You cannot plan when inspiration will come to you or make a calendar of when to work or you will end up having problems. Those who do end up on two boats. In one there are those who advance frustrated and disappointed at not being able to keep up and because they are overwhelmed, and in another those who cancel the project because they launch the demo when it was not yet ready. Sometimes they even advance to the production phase dragging their deficiencies. 80% of the errors in a video game come from pre-production. "

He has always been very critical of the early PlayStation 3, Sony's darkest era. "

He has always been very critical of the early PlayStation 3, Sony's darkest era. "

The most critical Cerny

As his method spread across the industry and he collaborated on the Jak and Ratchet & Clank sequels, Sony was beginning to think of the successor to PlayStation 2. Shuhei Yoshida, by then SCEA vice-president, noted Cerny's name as possible specialist to consult. Yoshida was concerned about the cost of the developments, which seemed to be skyrocketing, and although Ken Kutaragi had not had Cerny for the design of the console, he agreed to put him in charge of a group of specialists who would help the studios use and leverage maximize your new technology. Thus was born the ICE (Initiative for a Common Engine), which was based on the technical exploits of Naughty Dog (where it still has its headquarters) and was a working group whose main objective was for the different developers to share information and resources. Although the studios had been working at their own risk and until that moment, the complications of the chip cell of PlayStation 3 forced them to join, to truly feel part of a family, supported and endorsed not only commercially, but also during the creative process. "The cell was like a Rubrik's cube," Cerny would declare. “Developing was more costly in time and resources than ever before. Anyone living those years understood the importance of collaborating with others, the value of conversation, also with third parties, and the importance of hardware and software going hand in hand. ”

This Cerny taunt has to do with the origins of PlayStation 3, where although it was allowed to be, it had neither voice nor vote. "There were long periods of time in the development room that if someone had some sort of background and experience in video games, that was me," admitted Cerny. Years later, remembering what happened, he would be even more critical: “The PlayStation 3 problems were 99% hardware and 1% software. 2005, 2006, 2007 … it was a tough time in business, but it helped us establish the culture we have today. ”

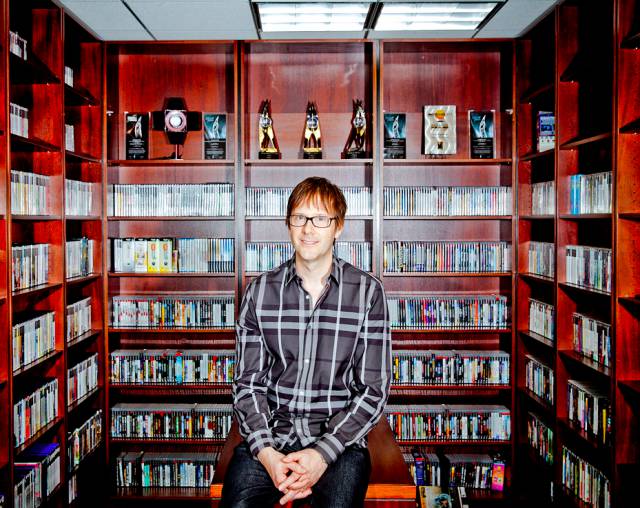

Mark Cerny with his collection of PlayStation 3 games.

Mark Cerny with his collection of PlayStation 3 games.

PlayStation 3 grew dwarfs

Another example of how things worked then has to do with E3 and was told by Yoshida himself. Just a couple of weeks before the typical Los Angeles conference, he picked up the phone and was told that the PlayStation 3 controller was going to wear a motion sensor and that he was going to demonstrate it during the act. "What ?!" was all he could say. I'd never heard of such a feature before, and that makeshift move resulted in Warhawk's disastrous demo. "With PlayStation 3 we were in the world of Ken Kutaragi. We did everything he said, even in command. He said "This is the future" and there was no debate, "revealed over time Toshimasa Aoki, one of the main architects of the Dualshock.

Between some things and others, and as a result, PlayStation 3 came out a year after its rival, Xbox 360, and being 100 euros more expensive. It only had 12 launch titles (the poorest initial catalog in Sony's history) and several developers publicly complained about the difficulties of working for the console because of the chip cell. According to some estimates, when PlayStation 3 went on sale, Sony controlled 70% of the market. Siete años después habían claudicado ante Nintendo y la cosa estaba igualada con Microsoft. La consola había estado 32 meses consecutivos por detrás de Xbox 360 en las listas de ventas de Estados Unidos. Sony había pecado de soberbia y aún así acabó remontando. La consola superó (por poco) a la de Microsoft aquella generación, más igualada de lo que nadie hubiera predicho. Cómo no, en eso tuvieron mucho que decir algunos de los juegos en los que colaboró el propio Cerny: Resistance: Fall of Man (2006), Uncharted: Drake's Fortune (2007), God of War III (2010) y Killzone 3 (2011). A Ken Kutaragi se le ofreció una pronta jubilación y la división quedó en manos de Kazuo Hirai y Shuhei Yoshida, ambos con una gran relación con el diseñador. “Es un poco surrealista que de pronto conociera al jefe de Sony de cuando solíamos beber después de conferencias como la de 1998”, bromeaba Cerny.

Aunque tuvieron sus más y sus menos, sobre todo en la época de PS3, Cerny siempre ha creído que Kutaragi "era un genio". En la foto, de 2014, éste recibe un premio a su carrera junto a (de izquierda a derecha) Riley Russell, Shawn Layden, el propio Cerny y Shuhei Yoshida.

Aunque tuvieron sus más y sus menos, sobre todo en la época de PS3, Cerny siempre ha creído que Kutaragi "era un genio". En la foto, de 2014, éste recibe un premio a su carrera junto a (de izquierda a derecha) Riley Russell, Shawn Layden, el propio Cerny y Shuhei Yoshida.

El nacimiento del arquitecto

Cerny siempre se ha mostrado respetuoso con la figura de Ken Kutaragi y su trabajo en las primeras consolas de la marca (“era un genio”), pero también sabía que PlayStation necesitaba un cambio si no quería volver a pasar por lo mismo. “Cuando PlayStation 3 salió a la venta empezamos a hacer una autopsia de la consola y el resultado fue brutal. Era muy, muy difícil para los diseñadores hacer juegos para ella. Yo no podía dejar de pensar que tenía que haber un camino diferente. Debía haber un hardware en el que hacer juegos fuera algo natural”. Esta idea fue creciendo en Cerny, que se pasó todas las navidades de 2007 estudiando “la familia x86”. Desde su invención allá por los años 70 hasta los últimos avances habidos. Todo con una voluntad y una energía de la que ni él mismo era consciente. “Sacrifiqué mis vacaciones para estudiar sobre una parte de la consola en la que yo ni siquiera tenía que trabajar y la cual no iba a ver la luz hasta dentro de cinco años. Esa pasión y ese entusiasmo hicieron que quisiera sumergirme de manera mucho más profunda en la nueva consola”.

Así, en 2008, Cerny se lanzó y atrevió con un pitch a Sony sobre el rumbo de la compañía y por qué tendría que ser él quien hiciera PlayStation 4. “Pensé que era la única persona con el background necesario. Había desarrollado videojuegos, pero también había estado muy metido en temas de hardware, al que había dedicado mucho tiempo, y además era bilingüe”. Siguieron meses y meses de reuniones con los distintos ejecutivos de la compañía (“muerte por Powerpoint”, recuerda él). “Sabía que era un poco atrevido, pero fui a ver a Yoshida y le hice un pitch de la idea. Para mi sorpresa dijo que tenía razón, así que fui a Kazuo Hirai e hice lo mismo. También aceptó, así que fui a ver a Masa Chatani, que era el CTO de la división (Chief Technology Officer) y para mi asombro también me dio el sí”. Lo había logrado. Sony accedió y le convirtió en arquitecto de la plataforma. “La gran decisión que tuvieron que tomar entonces era si seguir como hasta ese momento, con gente de hardware llevando la parte de hardware, o si también había que contar con desarrolladores de videojuegos en esa tarea”.

Cerny iba en serio con su nueva visión de las consolas. Quería desarrollos más fáciles y herramientas rápidas y sencillas, en la línea de la arquitectura que daba vida a los ordenadores de Microsoft. Visitó los 16 estudios first party que tenía Sony y a otras 16 desarrolladoras third party para escuchar su opinión y recoger peticiones, algo que Sony nunca había hecho hasta ese momento. “Empezamos un proceso más abierto, más colaborativo. Hubiera sido impensable en 2004 visitar a más de 30 desarrolladores para saber qué era lo querían ver en nuestro nuevo hardware. Al principio algunos ni se atrevían a decirnos la verdad y solo nos hacían la pelota”. Aquella vuelta mundo acabó con un acuerdo con AMD, el adiós al cell y la bienvenida a un chip x86, como los que usaban los ordenadores por entonces. Y por supuesto, sacó provecho de la experiencia previa que os hemos ido narrando. “La filosofía era la misma que en Atari, con los arcades. Queríamos un sistema que fuera fácil de aprender y difícil de dominar”. El resultado está a la vista de todos. Las diferencias en cuanto a dificultad de desarrollo se dejan ver en el catálogo de lanzamiento de PlayStation 4, que salió con 22 juegos y añadió otros 100 en apenas mes y medio, por los 12 con los que había salido PlayStation 3. Además, la consola fue 100 euros más barata que Xbox One, su competidora directa. Sony volvió a imponerse con holgura en lo que a ventas se refiere y PS4 ya es la consola más vendida de la compañía, solo por detrás de PlayStation 2. (Para conocer a fondo todos los detalles de su construcción y desarrollo, no podemos más que recomendaros una y otra vez este estupendo artículo de Gamasutra, 'Inside the PS4'.)

Otro galón, PlayStation Vita

PlayStation 4 no es la única medalla que cuelga de la chaqueta de Cerny. Aunque no se dio a conocer hasta tiempo después, también estuvo detrás de PlayStation Vita, tal y como se confirmó en 2011. “Si PlayStation 4 estaba basada en el concepto de hacer una arquitectura de PC de gama alta, con PlayStation Vita era lo mismo pero en relación a los móviles”, contaba Cerny. Sony nunca ha tenido el mismo interés en hablar de su segunda portátil, quizás por las ventas que tuvo (entre 10 y 15 millones, lejos de los más de 80 millones de PSP), pero desde luego, si la consola no tuvo el ciclo de vida esperado no fue por culpa de su hardware, muy aplaudido en aquel momento. Estaba lleno de ideas e innovaciones: los dos sticks en una portátil, la pantalla trasera, la resolución y potencia gráfica que era capaz de aguantar… Por no hablar de que servicios como el cross play o el reciente Smart Delivery tienen un claro antecesor en la relación que hubo entre PS4 y PS Vita, que lo compartían todo. Algo que Cerny recuerda con cariño. “Yoshida y yo hicimos un pitch sobre esas funciones el mismo día. Fue una coincidencia maravillosa. Ambos habíamos llegado a la conclusión de que la relación entre ambas plataformas tenía que ser muy fuerte”. El desarrollador había pasado a ser clave en cada nuevo paso de Sony.

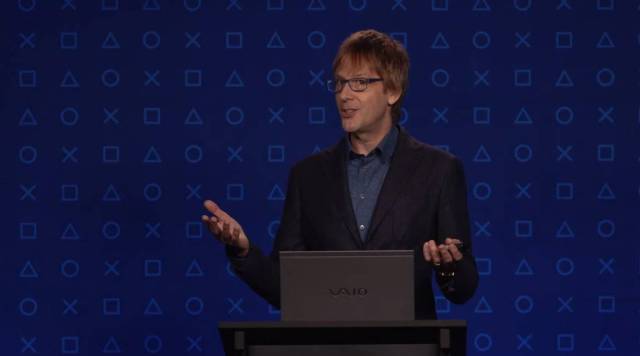

La última foto que hay de él, de 2020, durante la primera presentación oficial sobre PlayStation 5, la tercera consola que llevará su firma.

La última foto que hay de él, de 2020, durante la primera presentación oficial sobre PlayStation 5, la tercera consola que llevará su firma.

El hombre del renacimiento y la futura PS5

Llegamos al final de este repaso a la vida y obra de Mark Cerny. No sabemos qué le aguarda el futuro ni cómo le irá con PlayStation 5, pero a sus 55 años, Cerny ha hecho méritos suficientes en la industria como para convertirse en una parte fundamental de su historia. Sin él sería imposible entender cómo funciona la actual Sony, o el golpe sobe la mesa que ha dado PlayStation 4. Pero no solo eso, sino que también nos hubiéramos perdido juegos y personajes inolvidables. Sonic, Crash Bandicoot, Ratchet & Clank y muchos otros a los que ayudó y aportó su granito de arena. A pesar de ser un espíritu independiente, Cerny no ha hecho las cosas solo, está claro, pero es evidente que las cosas tampoco se hubieran hecho así sin él. Siempre habrá motivos para la burla. Que si Knack, que si la ventilación y el ruido infernal que provoca el diseño de PS4, que si la “pérdida de potencia” de PS5 con respecto a Series X, que si “hace funciones desaprovechadas” como el pad trasero de Vita y el panel táctil del Dualshock 4… Siempre los habrá. También surgirán historias sobre cosas qué pudo hacer mejor, tal y como ha pasado con Kutaragi. Pero nada podrá emborronar semejante legado, más importante de lo que la gente piensa y resumen de uno de los mayores talentos de esta industria. Alguien que ha contribuido a que una de sus frases favoritas se haga realidad. “No hay mejor época que ésta para ser gamer”.

Mark Cerny, 1984. "¿Por qué todos los jugones sonríen igual?".

Mark Cerny, 1984. "¿Por qué todos los jugones sonríen igual?".