From Donkey Kong to the recent The Last of Us: Part II, we explore the art of storytelling (and participation) in the stories of the medium.

Let’s assume a story. One that takes us to a fantastic world where landscapes such as forests or towns may be familiar, but are inhabited by monsters. The protagonist ventures among them, doubting whether they will be dangerous or hostile. Sometimes he runs away; others, fight. Along the way he also makes friends with someone. Now suppose that this trip is not narrated in a book, a comic or a movie, but in a video game and that, therefore, the controller creates an invisible thread between our actions and those of the protagonist. Would history change? Even in a predefined story, where every major event is painstakingly orchestrated by the creators, having that kind of control favors both immersion and connection with the protagonist. Although of course, being an interactive medium, it also opens up new possibilities that others do not have. That of giving us the role of co-author to influence and change, to a greater or lesser extent, the evolution of the narrative.

It is a subject that has been dealt with since almost the dawn of the medium, and that will continue to be dealt with over the decades because the stories and the ways of telling them will not go anywhere. On the contrary, they will continue to evolve at the same time that the environment evolves, still young if we compare it with the others mentioned above, but with a potential already operating at full capacity for some generations. So today, that we are officially in a new console generation (PlayStation 5 was released yesterday and Xbox Series X has been with us for more than a week), we are going to take the opportunity to reintroduce some general notions, recall its evolution and delve into some samples popular of recent times. A history of stories, worth the redundancy, and its abilities to connect with the players.

Gorillas and princesses: Narrative as motivation

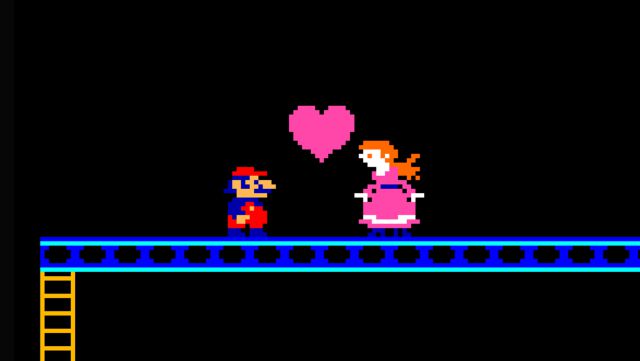

It is paradoxical to think that much of this goes back to Shigeru Miyamoto, a creative hyper-focused on the playable facet and in charge – along with his collaborators – of establishing many mechanical bases for platforms, adventures and the medium in general, both in 2D and 3D. Now it is difficult to think of him as someone concerned with the arguments, and some of his disagreements with other Nintendo employees are even famous when it comes to limiting that facet or linking it more directly to playable functions, but it was this utilitarianism that gave origin to one of the first emblematic stories of the medium. Initially conceived as an adaptation of Popeye, when left without a license, Donkey Kong was rethought as the conflict between a carpenter and his pet, the homonymous gorilla who kidnapped his girlfriend and climbed buildings in a slightly camouflaged reference to King Kong.

Needless to say, this premise is now practically the most basic thing a video game can aspire to – sports cars aside, and even there there are exceptions – but in an era defined by arcade games like Pong, Space Invaders, Pac-Man or Defender, Donkey Kong he moved the objective from the mere accumulation of points towards the resolution of a narrative conflict: to rescue Pauline. In time, Pauline would be relieved by Peach, and Peach by Zelda. And although Miyamoto has been watching for years as his pupils direct new installments of the sagas he created in the 1980s, Breath of the Wild still uses this simple triangle to build an adventure of epic scale, where the player can embark on the resolution of many other small narrative arcs, but where sooner or later you need to return to the center of the map to solve the one starring Link, Zelda and Ganon.

This decision, questioned by some who have seen the medium evolve towards more elaborate plot premises – including other installments of the Zelda saga itself – still makes it clear that “saving the princess” is not so much a story as a goal. A motivator that sets a clear objective on the horizon, but does not deter us from participating in other tasks, such as disguising ourselves to infiltrate a village of entry allowed only to women, helping to build another where all the races of Hyrule converge or finding the Sword Mistress left safely by the princess before leaving for the castle. All of them and many others can be faced in different order or even completely ignored, making their discovery and resolution a unique narrative aspect, only possible in video games.

Dragons, dungeons, and organic storytelling

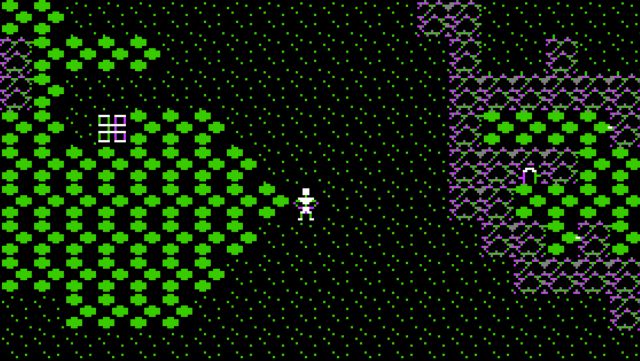

Of course, to understand the origin of that freedom, you don’t have to look at Donkey Kong, but rather at a game released a month earlier, in June 1981: Ultima. Similar themed text adventures such as Adventureland or Zork had proliferated in the computer market during the 1970s, but Ultima was a key turning point in establishing RPGs as exploration and combat games in the context of a grand adventure. medieval fantasy — with some science fiction also spiced up for ultimate nerdy delight. Although its initial popularity was perhaps not comparable to that of Donkey Kong, based on sequels and re-releases it expanded its reach and favored the appearance of more and better exponents of a new way of understanding both the gameplay and the narrative, adapting the games board of Dungeons and Dragons inspired by Tolkien mythology (Ultima’s forerunner, Akalabeth, even took its name from a chapter in The Silmarillion).

Although abstract in their visual properties, this lineage was momentous for stepping outside the more claustrophobic confines of the roguelike and allowing the player to insert himself as himself into vast virtual worlds. Different races and classes to choose from, towns with taverns and shops to trade, the possibility of accepting missions such as hunting monsters or, why not, also rescuing some princesses. The plot involved the search and activation of a time machine to travel to the past and defeat an immortal villain before he was (an idea that years later would borrow the first Final Fantasy), but what really made the difference was that ability to customize our story at the same time as the character, exploring, finding places that improve our attributes, trying different weapons and spells, stealing items from stores, going into combat with guards, getting different methods of transport, etc.

Naturally, in that primitive form there were still quite a few limitations around what to do and how to do it, but games like Ultima not only took the first steps towards the role as a genre, but also towards a more organic narrative. Despite being one of the most modern forms of storytelling, videogames recapture the more spontaneous and flexible nature that the act of storytelling had in its origins, when it was done orally. Many centuries ago, chroniclers and poets recounted wars, myths or anecdotes out loud, adorning and altering them in the process. With the writing came another level of precision, the story became constant. The main plots of video games reflect this, but between the lines they can leave large spaces to be filled with phrases specific to each player, from each game, the result of interacting in different ways with NPCs, entering different places in different order or living situations that are not expected. -programmed, but the product of variations in the AI, the mediation of other people or the player with the systems.

The environment as a narrative

This kind of freedom has also been a breeding ground for the elaboration of mythologies and backgrounds (or the ingrained English term lore) that complete the image of the worlds piece by piece, as if it were a puzzle. From Elder Scrolls books to Souls item descriptions to System Shock audio recordings, video games can optionally and non-intrusively expand their universes. Layering letters or emails creates narrative tangents that the player can ignore if they want to focus on the action, but they reward those hungry for information who actively seek them out and fill in the gaps left by sequences and dialogue with their imagination. It is another interactivity tool that escalates to the next level when the scenarios themselves tell the stories.

Play spaces are often designed to display the available mechanics and the challenges built around them (be it navigation, combat, logic, etc.), but their architecture is rarely limited to a single purpose, serving aesthetic functions as well. , narrative or evocative. The Forbidden Land of Shadow of the Colossus, for example, stretches for miles and miles without apparent need – from a practical point of view – to accentuate the solitude of the journey, the silence between battles, the mystery of ruins that reveal that once It was populated by man although now only small animals and the colossal creatures that give it its title remain. The streets of Rapture, on the other hand, are overflowing with bloodstains, graffiti and trash on every corner, enough to show that the underwater city of BioShock went from utopia to dystopia in a rather drastic way even if the studio dispensed with the inherited recordings. by System Shock.

This ability to narrate through the scenarios, of course, is not something exclusive to this medium, anyone of a visual nature can convey ideas —context or subtext— through the scenography. But video games are unique in that they allow the player to “enter” virtual space, move around, and satisfy the most prying instincts, to the point that we often see titles built entirely around this symbiosis between history and place. : Gone Home changed the fantastic worlds for an ordinary house where the protagonist reconnected with her absent family through notes, diaries and objects; while Return of the Obra Dinn and Outer Wilds enhanced the detective work using spaces (a sailboat without survivors and a complete planetary system) and mechanics (the exploration of the deaths of the crew members in the first and of time loops highly influenced by physical laws in the second) more creative to curdle experiences impossible in any other medium despite its relative mechanical simplicity.

Character driven narrative

Of course, there is hardly a story without characters, and many times they are the real engine, the hook that catches us despite a simple plot, some scenarios with little detail or a gameplay with room for improvement. Precisely last month, No More Heroes – and its sequel – came by surprise to Switch, a game whose approach may be reminiscent of Shadow of the Colossus (breaking through to ten opponents and defeating them), but which, far from trying to offer the majesty of its world and his creatures, he recreates the histrionics of Travis Touchdown and a cast of murderers each more extravagant. It’s a case of the manual, as the end goal is frivolous and only beneficial to Travis, and the city of Santa Destroy offers little value in terms of background or organic narrative. But still, it works thanks to the script and the constant gloating in the absurdity of the situation and those involved in it.

This notion of characters as a narrative core can also be traced back several decades in time, with great samples between the graphic adventures of LucasArts (Monkey Island, Sam & Max) or the greater dramatic weight that Squaresoft gave to his role-playing casts (in 1991, Final Fantasy IV already had a vision quite similar to the current one), although the progress of technology and the standardization of dubbing has given new wings to this facet. This brings us to another recent announcement, that of the relaunch of the Mass Effect trilogy next spring, because it symbolizes how this realignment of priorities has also been applied in Western RPGs, a genre traditionally more concerned with letting the player make the protagonist an avatar. to insert the motivations that you consider appropriate.

Created by BioWare, the studio responsible for role-playing sagas as emblematic as Baldur’s Gate, Neverwinter Nights or Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect put us in the shoes of Commander Shepard, the protagonist whose first name, gender or aspect we could change to our taste, but which persisted as its own character, with a certain degree of autonomy as it was governed by a circular interface that converted brief thematic options into complete dialogues, dubbed and acted like those of the predefined characters. With this wheel, naturally, a morality system was also implemented for the player to modulate the personality of their Shepard, but it did not allow radical deviations as Knights: virtue and rebellion were nuances of a character that, at the end of the day, still he had a fixed position as a hero of humanity in a galactic conflict.

This, of course, does not mean that there were no meaningful decisions either. Both the future of love relationships and the future of entire races depended on our use of the dialogue system, sometimes with consequences not only within one installment, but throughout the trilogy. Therefore, while the system was not as versatile as other RPGs, it was a fairly successful attempt to pose dilemmas to the player while keeping a charismatic protagonist on screen, capable of carrying a more cinematic narrative on his shoulders. It is an idea that we have also been able to see deployed in The Witcher, a saga where the sorcerer Geralt has been increasingly defined as his own entity, and in narrative adventures as varied as The Walking Dead, Life is Strange or Until Dawn, where the player decides and manipulates the lives of characters with well-defined personalities.

The influence of cinema

The reference to cinematography invites us, of course, to jump to Metal Gear Solid and discuss both the influence that cinema had on Hideo Kojima and Hideo Kojima on video games. Sequel to two 8-bit installments, Solid marked the leap of the saga to three dimensions, but it made history above all for its staging, with credits accompanying the first playable minutes, use of abundant dubbed sequences with special attention placed on the blocking and use of the camera, as well as an adult and dramatic plot with its fair share of twists. Of course, there was also a great sneak-peek action game underneath – or alongside – it all, and the narrative left room for self-referential moments (like a boss’s comments on save files for other Konami titles on the card. memory or the need to check the back of the box to find a character’s radio frequency), but in terms of sequences and performances it set a new standard for this class of productions.

In a way similar to how Final Fantasy VII, despite being part of a long list of high-quality and successful JRPGs, solidified the potential for long narratives reminiscent of media such as manga or anime, Metal Gear Solid opened new doors for the permeation of cinema. Even preceded by other adult games with sequences and dubbing, Solid cemented the figure of Hideo Kojima as a director in a sense more typical of the so-called seventh art and that of David Hayter as an actor with also a significant degree of authorship over the character played (although here Let’s associate Solid Snake with the voice of Alfonso Vallés until the arrival of PS2). Today, both figures are still relevant: Kojima has surrounded himself with stars of a more filmic profile for Death Stranding, while actors such as Troy Baker, Nolan North or Laura Bailey dominate the blockbuster scene and are often as or more recognized than the characters they embody or their writers.

It should be noted that cinema and video games found intersection points very early, either due to aesthetic influences (Snatcher, by Kojima himself, did not hide his references to Blade Runner) or due to direct adaptations (continuing with Blade Runner, that universe too had his official graphic adventure with movie talent involved). But the establishment of the three dimensions and works such as Metal Gear Solid favored a refocusing on the use of the camera, event planning, script writing or the use of actors in unpublished material, but clearly influenced by methodologies and iconographies of the medium. brother. Grand Theft Auto, for example, finds as much inspiration for its characters and sequences in gangster movies as it does in American society itself that it parodies, something that is later transferred to mission design; and Uncharted not only takes from Indiana Jones the concept of treasure hunters searching for relics all over the globe, but also its set pieces and interpersonal dynamics, which it implements both in traditional sequences and in sections where the player has a certain degree of control, but must let them events take place totally or partially based on the script.

Ludonarrative Dissonance and The Last of Us

Speaking of Uncharted, we come to what was a fashionable concept for the past generation (technically, two years ago). For those who missed the conversation or no longer remember it, the term ludonarrative dissonance was coined to refer to instances in which the story presented through sequences or dialogues created some kind of friction or even contradiction with the events in which the player had control. Precisely Grand Theft Auto IV and Uncharted were two of the objectives pointed out by some in this debate, alluding to the fact that the extensive count of damages and corpses that both Niko Bellic and Nathan Drake could accumulate contrasted with their respective characterizations (in the case of the former, by his explicit intention to leave that life behind; in the second, because the jovial tone deprived the violence of almost any impact).

The debate, although with its merits and interest at an academic level, ended up dying out because, when push comes to shove, convenience rules: setting a goal as urgent in an open-world game and then letting the player hang around and invest hours in secondary tasks it can break the narrative immersion, but the alternative would deprive a freedom that developers and users agree to as part of the tacit contract. Even so, despite some abuse or misuse, the concept favored the appearance of games like Spec Ops: The Line, where the text explicitly deals with this kind of dissonance, or The Last of Us, where Naughty Dog herself created a world of extreme violence also in the narrative plane, thus reinforcing the playable mechanics that the player needed to survive.

The Last of Us not only had dramatic sequences, with deaths that overwhelmed the player like a truck, it also dispensed with conveniences such as self-regeneration of life and rationed both ammunition and resources that allowed to create medicine cabinets or weapons to encourage meticulous exploration of the scenarios and promote a strategic entry into combat. It also introduced a companion, Ellie, who, while creating her own form of dissonance by being invisible to the enemies we were supposed to protect her from (at least while the playable character, Joel, was hidden), created a clear motivation to complete the game. travel. Thus, the princess who was waiting in the castle or on top of a construction became an adoptive daughter that we had to take care of every step of the way, justifying narratively and playably all the actions that we needed to do so.

The experience accumulated during the first three Uncharted allowed the studio to take both the PS3 towards its technical ceiling and the work with actors to a new level, building with them a narrative more similar to the serial format than to the feature films. Joel and Ellie were introduced to the player and built their relationship step by step: first, for several days almost uninterrupted; and then, for several seasons to speed up somewhat – but not too much – its dynamics, both in traditional sequences and highly scripted Uncharted events, as well as in dozens and dozens of “spontaneous” dialogues – some optional – with which the game filled the transitions between modules in which action and stealth were deployed. Making the world such a hostile environment, with zombies and normalized murders, allowed to create drama from moments that in other games would be skipped to go to the good, because here the good thing was the trip and not the destination. An expression so cliché that it almost hurts to write it, but which, like other genre conventions used for its characters and situations, took on new meaning in this context.

From here we will gut key events from both The Last of Us and its sequel, The Last of Us: Part II. Those who have not completed both titles should jump directly to the last section and / or return after playing them.

The Last of Us: Part II and empathy

Although it is revealed that at some point during the two decades between the start of the viral outbreak and the present adventure, Joel was also a participant in the assaults, torture and murders so common in the new post-apocalypse order, the violence used by him on screen —With or without our assistance — always responds to Ellie’s instinct for self-preservation or safety. In a perhaps not very subtle, but very effective maneuver, the first The Last of Us opens with the tragic death of his daughter Sarah and then develops, in a methodical and at the same time natural way, a new father-child relationship, this time before the eyes Of the player who, even though he may be surprised or shocked when Joel resorts to his torture tactics to elicit Ellie’s whereabouts during the winter episode, hardly creates much friction about her characterization, motivation or morality.

The end, of course, puts the connection to the test more when Joel bursts into the operating room to forcibly stop the operation that can find a cure at the cost of the girl’s life. There is no choice, but – again, for many – neither dissonance because the game had been more about the strengthening of that relationship (narrative driven by characters) than about the possibility of the vaccine (narrative as a goal). For a brief moment, Ellie becomes the metaphorical princess to be rescued and, although the way to morally rationalize all the implications of that event may vary from player to player, the play concludes a few minutes later, in a clearly bittersweet tone. despite the survival of both protagonists, but consistent with the playable story.

If The Last of Us did not have a sequel, or it focused on other characters, Ellie’s visible regret at Joel’s final lie would formally close the story and the rest would be left to the imagination of each one. But, for better or for worse, Naughty Dog decided to pick up the thread where it left off and the result has been both the most acclaimed game (notes aside, it leads the recently announced nominations of The Game Awards) and the most controversial of this year. it is almost time to close. The debate around Part II was more heated than any of those caused by the ludonarrative dissonance in the days of its prequel and, although some points of contention have their origin in factors external to the game – sometimes rooted in problems of a psychosocial nature that they largely escape the subject of this text— others are easily traceable to the use that the study has made of narrative tools.

In a decision that demonstrates almost the same degree of ingenuity as of courage, Joel is executed in the opening bars of the game by Abby, a new character who, hours later, is revealed as the daughter of the surgeon that Joel himself murdered at the end of the first The Last of Us. From there, both Ellie and Abby embark on two parallel adventures, which take place simultaneously, but the player loops through sequentially: the first half of the game focuses on Ellie and her search for Abby to repeat the cycle and take revenge even if it implies falling into a spiral of self-destruction; For her part, the second half centers on Abby, who becomes embroiled in a larger-scale conflict between two rival factions and, not unlike Joel during the foreplay, regains her humanity through her relationship with the younger and more vulnerable brothers Yara and Lev.

This game of parallels, although not without its conveniences, gives rise to a more elaborate, original and unpredictable argument than the previous one, but it also has a much greater potential for friction that is accentuated by the fact of being narrated in an interactive medium . Despite the fact that Joel carries even more reprehensible actions on his shoulders (massive murders and deprivation of a possible cure for a problem on a global scale versus the search and murder of the individual responsible for such acts), trying to generate a similar empathy for Abby Following the opposite process is, as we said, brave and naive in almost equal parts because it underestimates the extent to which the way of constructing the first story playable and narratively conditioned the perception of Joel. In a stroke of irony, Naughty Dog was so efficient at alleviating dissonance that it made it difficult to later turn to a more gray and relativistic narrative in the sequel.

It is a complication to which is added a much more fragmented structure, where the resolution of the theater’s cliffhanger (end of the third day in Seattle) is postponed for hours, and where the narrative perspective fluctuates too much due to alternating so much between characters with opposite motivations, as between eras (via flashbacks) where their mental states and interpersonal dynamics are also different. This allows us to get to know Ellie and Abby in greater depth, something that, in view, has had an effect on many players. But it has also alienated others, who perceive its role as taking turns holding two puppets whose strings rise far beyond our reach. This conflict reaches a critical point in the final duel, where Ellie insists on facing a tortured and malnourished Abby and the player must deliver stabs because the alternative involves failing and charging the previous control point.

The sequence ends with Ellie letting Abby go after a moment of self-awareness that pushes her to stop the cycle of revenge, although it is a climax potentially undermined by the fact that we do not have any control over the situation (some might want to culminate revenge, others letting Abby go without fighting or even leaving Dina’s farm); that this kind of absolution has already been given before and then reverted; that Ellie and the player are not in tune about their knowledge of Abby (humanization work with her father, Owen, Yara or Lev is only perceived by us); or that the trail of deaths that has brought him here does not prevent the cycle from continuing if the scriptwriters so decide in a hypothetical third installment. To both its merit and detriment, Part II tells a very specific story under very specific conditions, which in the context of a “video game narrative” can be settled with limitations or even contradictions, but in that of a work of authorship with A message to share can be as or more interesting than its predecessor. As always, from there it is up to each one to draw their own conclusions.

Undertale and the choice with consequences

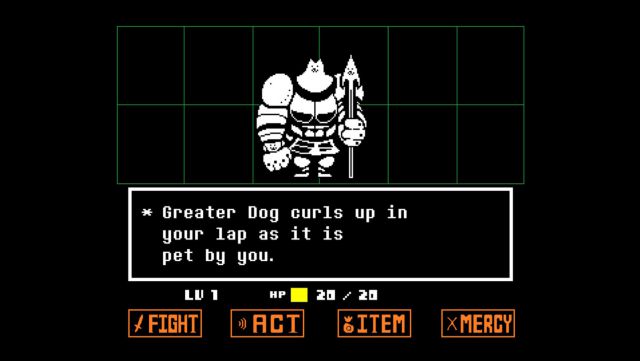

Before closing, and as a counterpoint to the drama – in more ways than one – of The Last of Us, we are going to change registers with an indie that recently celebrated its fifth anniversary. Created for the most part by developer Toby Fox, Undertale is a 2D RPG in which the player plays a mute avatar and tries to make his way through an underground world populated by monsters that react differently to the presence of a monster. human among them (the Papyrus skeleton wants to hunt us down, but its affable nature soon reveals it as harmless; the fish-warrior Undyne, on the other hand, pursues us relentlessly and does not hesitate to finish us off). One of the first that we find is the maternal Tauriel, who not only protects us from other monsters, but also urges us to interact with them in a friendly way through a command system that changes contextually and works like little logic puzzles (caress a canid, laugh at the jokes of an aspiring comedian, compliment monsters with esteem problems, etc.).

Pero pronto queda claro que el plan de Tauriel consiste en adoptarnos aunque no lo queramos, impidiendo el progreso a menos que nos enfrentemos a ella. Sin embargo, su interfaz no dispone de esos mismos comandos para intentar una solución diplomática, así que el jugador se encuentra a sí mismo ante la disyuntiva de usar los métodos tradicionales de los RPG (atacar y bajar su vida) o insistir en la opción de «Mercy» (misericordia) una y otra, y otra vez, hasta que Tauriel desista. Dado que este procedimiento es contraindicativo según las convenciones habituales de videojuegos, el resultado para la gran mayoría de jugadores, al menos en su primera partida, será acabar con Tauriel y quedar automáticamente privados de ver el final pacifista.

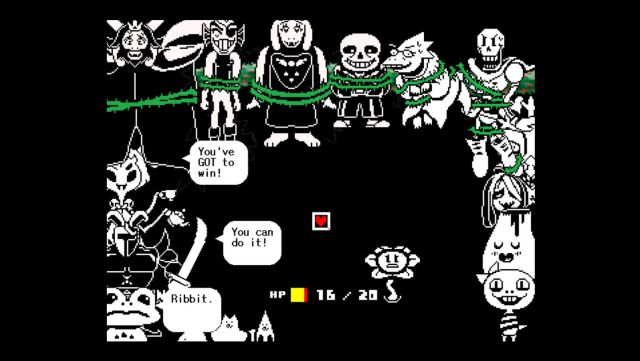

Si lo sabemos de antemano o reparamos en ello, podemos evitarlo o revertirlo cargando la partida previa (caso en el que otro de los personajes principales, Flowey, lo comenta para que tengamos claro que el juego registra más de lo que parece y no duda en romper la cuarta pared), aunque el dilema se extiende al resto de la partida: no eliminar a los monstruos puede ser más satisfactorio a un nivel personal, pero derrotarlos mediante fuerza bruta tiende a ser más sencillo y nos reporta experiencia que aumenta los atributos y, como buen RPG, facilita las cosas cuando llegan los jefes más exigentes. Sin embargo, este atajo hacia los créditos es uno que nos bloquea contenido, pues solo dedicando el tiempo y el esfuerzo a simpatizar con todos conseguimos acceder a los mejores eventos, en los que participamos en citas, descubrimos al detalle el trasfondo del mundo, cambiamos para siempre la vida de sus habitantes y alcanzamos el emotivo final que ata todo con un lacito.

Claro que también podemos hacer justo lo contrario y probar la ruta genocida, donde exterminamos a literalmente todos los monstruos —los combates aleatorios dejan de activarse con el tiempo— y la atmósfera cambia para crear una fantasía de poder malévola en la que solo dos héroes, amigos en una partida alternativa, son capaces de hacernos frente. De hecho, se trata de las dos batallas más difíciles que podemos encontrar en cualquiera de las rutas, siendo la segunda, además, uno de los mayores retos que alberga cualquier videojuego en general. Porque una cosa es poder ser un genocida y otra deber ser un genocida. Undertale lo deja claro y, aunque tanto la narrativa como la jugabilidad lo permiten, ambas se encargan de castigarlo. Eso sí es algo que definitivamente no está al alcance de otros medios.