SadSquare Studio picks up the baton from Kojima and Konami to convert the concept of P.T. in a complete and chilling horror game.

So long and hard it has been said about P.T. and the subsequent cancellation of Silent Hills that, every time the conversion is resumed, one has the feeling of being reopening and preventing a wound still fresh in the collective imagination from healing. However, days like today show that his story, although incomplete, is cause for joy because of what he directly or indirectly favored in the middle. Months before its arrival on the PlayStation Store, Capcom had already planned Resident Evil 7 as a return to a more intimate horror with a first-person perspective, but the effusive reception of P.T. He finished cementing that path as the correct one and gave rise to the rebirth of everything great in a saga that had suffered a strong identity crisis for years.

Other creators with no comparable media or big-name franchises to rekindle chose to recreate the demo itself when Konami decided to cut its losses and remove it from the virtual store, or to produce new games inspired by the work of Hideo Kojima from scratch. Allison Road, unfortunately, suffered a similar fate and ended up disappearing from the map, but Visage, after a successful Kickstarter and a long season in Early Access, has finally finished its development and arrived in its final version on both PC and PlayStation 4 and Xbox One. A “Lucy” (episode premiered in October 2018) and “Dolores” (July 2019) is now joined by an unpublished third, “Rakan”, in addition to a parallel search to all of them that culminates in the definitive outcome . Visage is already a complete game and it’s time to evaluate it as such.

3 + 1: Variety of scares and concepts

Of course, despite being finished – beyond the corrections or changes that SadSquare Studio can still implement via updates – this episodic format remains one of the main features of Visage. The three chapters with their own names (Lucy, Dolores and Rakan) function as small independent adventures that, once activated, unfold and culminate in their own climaxes before allowing us to start any of the rest. The order, of course, is up to the player (we can start directly with Rakan even if it is the latest addition) and the structure, although quite defragmented if we compare it with classic exponents of the genre, allows both to create more familiarity with the house in which The bulk of the game unfolds as it then subverts that familiarity with new threats and design alterations.

This principle of subversion is tied to Survival Horror since its inception, where backtracking with newly acquired keys or pieces to solve puzzles was sometimes used to catch players off guard. Resident Evil made it an art and back to the time of the Spencer mansion and P.T. it took it to a fascinating new extreme by conceiving of its development as a constant loop through a corridor introducing subtle or major changes based on highly cryptic actions, of which we were often not even aware. For his part, Visage tries to create a hybrid that combines meaningful exploration of a multi-story residence with constant surprises, ranging from small scares (lights that go out, strange noises) to the descent into the most extreme paranoia when the chapters escalate. and the danger becomes more tangible.

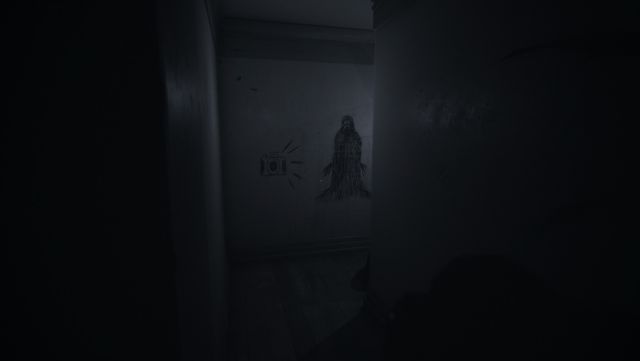

Entering one of these chapters interacting with one of the three objects arranged for it (the interface makes it clear which one and asks not to do it by mistake) is a necessary condition to access most of the house, which first adopts a type of exploration something more conventional and to a certain extent common – there are no missing keys and doors named to match – but then it turns towards its own events and dynamics, also entering a more psychological horror: depending on the chosen chapter, the game uses sound tracks, the appearance of new objects, blobs or even specters to guide us towards our objectives in a clearer way than PT, but with still room for cryptic situations or brain teasers.

The house, in fact, is partially transformed to suit each story. Although at the narrative level they are connected in a way that is largely up to the player’s interpretation, the building as a physical entity is the main link and uses changes in the decoration of some rooms to show that these stories took place at different times and with different tenants. As Dwayne, a mute protagonist whose chapter is not clearly named because it is the connecting fabric between the others (beginning, interludes and ending), we explore the house’s past in a figurative and literal way, interacting with the previous inhabitants and discovering first-hand the dramas they suffered before our arrival. It is a concept that not only allows you to get more out of your home, but also to approach different types of playable proposals.

Lucy: In the shadow of P.T.

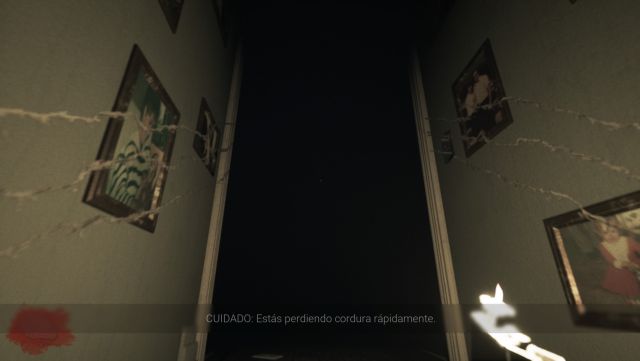

Having already established that the order is free, it is worth commenting first on Lucy’s chapter because it was released earlier and is the one that best illustrates both the influences of P.T. like the use of mechanics related to light. Also taking notes from Amnesia: The Dark Crescent, Visage implements a sanity meter that becomes visible as sanity is reduced by shocks (like a clock ticking, a TV that turns on itself) or staying in the dark. A little observation reveals that it works quite lightly, sometimes it allows you to go through unlit corridors without consequences and other times it accelerates abruptly to put pressure, but despite this it is a valuable element because it works in tandem with other systems that add more substance to gameplay than simple exploration.

One is the use of pills to regain sanity. These are found in small cans when exploring and are kept in what is known as a dynamic inventory – limited to five boxes – to be consumed in case of need. Taking into account that in Visage there is no life as such, the deaths when a creature grabs us are instantaneous, these pills are the closest we have to the management and use of healings from other games. Under normal conditions, appearances like those of Lucy herself are anticipated by light or sound effects (playing with headphones or a good audio system, beyond favoring immersion, is recommended for its great playable utility) and leave a generous margin to flee, but with low sanity they have a free hand to catch us whenever they want.

The other key system is the control that the player has over the lighting: practically all the lamps in the house have their switch, which can be activated manually to turn them on and create a cozy atmosphere, more similar to that of a game like Gone Home than any Silent Hill. However, some of these lamps do not work, introducing another management element through the replacement of bulbs that we find scattered, and they can also be turned off randomly depending on the level of sanity or certain predefined events. In that case —and it comes with special emphasis in the Lucy chapter—, the player can resort to candles —with their own plates and candelabras to be placed, and immune to paranormal phenomena— and to lighters that, in addition to lighting them, allow us orient ourselves in the midst of the most absolute darkness towards which we are sometimes irretrievably thrown.

These lighters have a limited duration and do not prevent the reduction of sanity, although they end up being our best allies, the item that can never be missing from the inventory, especially since the sanity indicator tends to lose relevance when the chapters move towards the exclusive areas: although they all start in common parts of the house, their progress always ends in areas where study poses different types of challenges or, why not say it, scares. In Lucy’s case, we end up wandering labyrinthine corridors where the lighters also stop working and the game requires using the flash of a camera to momentarily illuminate rooms where we meet a new friend. If someone does not like jump scares, this is surely the chapter that will make it happen the worst.

Dolores: Wickers from Classic Survival

The Dolores chapter, while not without its share of frights, is where Visage moves to the next level. Where it comes out of the shadow of P.T. and it comes close to what could have been a Silent Hills theorist stretching out his formula for several hours. Like so many other exponents of indie horror, the game still doesn’t implement combat, but the backtracking, use of inventory, and puzzle solving are reminiscent of some classics from the 32-bit era and immediately after, when the developers still thoroughly controlled what each camera showed. The progression is less cryptic and we do not depend so much on following “spectral tracks” or resorting to trial and error as on understanding which objects go where, what places we still have to explore and how the knot posed by design is untied.

As in the Lucy chapter, Dolores introduces her own sections, although they tie in a more natural way with the structure of the house, branching it out and giving rise to the most elaborate search tasks in the game. That said, the decision to disable several doors to create a bottleneck between the two main blocks (upper and lower) is also striking, which initially works in favor of that principle of subversion that we discussed earlier, but in the long run it can blow up backtracking somewhat by not allowing the alternative routes that the pre-alteration design did allow and requiring to cross over and over sections where the player is interrupted by brief transition sequences or is limited to walking forward.

It may not be as serious as it may sound in writing – it will depend on the pace at which each player feels most comfortable or on whether they are forced to make more trips than necessary due to losing track of their goals – but it is a small one. fissure in what otherwise rises as Visage’s high point. The chapter by Dolores and her husband aptly recaptures recurring Silent Hill elements such as impossible architectures, grotesque imagery, hellish environments and — to mark in a more real and profound way — everyday problems such as dementia and its effects on a family nucleus. It is something also covered in the Lucy chapter or other parts of the game (topics such as depression or addictions are inserted with few squeamishness or subtlety), but here it curdles its best form at all levels.

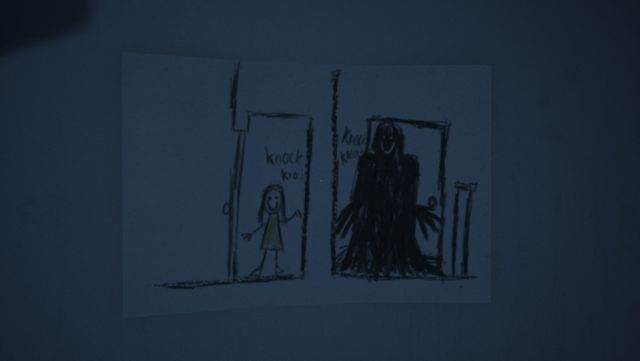

The fragmentation of a search into several simultaneous tasks, the ease with which you walk between hyper-realism and feverish delusions, the presence of puzzles that require you to pause to carefully decipher clues (written notes, audio recordings, drawings, etc.) or The use of a broader and more varied repertoire of items than keys, lighters or the camera makes this section practically justify the admission price on its own – it is also the longest of the group, requiring 3 to 4 hours to complete it for the first time. Of course, in the end it is up to each player to decide which chapter they prefer, but in this one it is quite easy to see the fundamentals for a sequel that not only rubs shoulders with indie horror references, but also with medium-high profile productions .

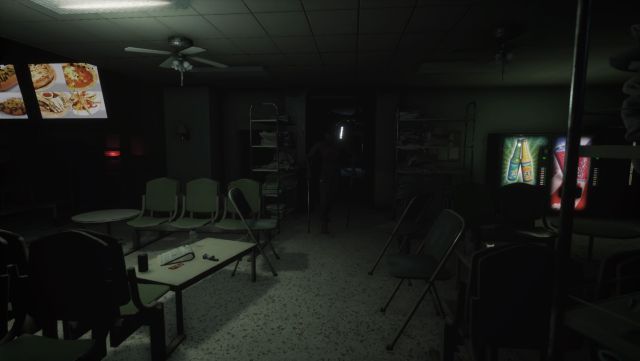

Rakan: Persecutions and effects

Speaking of indie horror we come to Rakan, the most recent addition and also the one that marks the most distances from the previous ones. Perhaps in an effort not to over-exploit the house, most of this chapter takes place in a hospital that, in its early stages at least, is suspiciously reminiscent of another Kojima game: The Phantom Pain. When it comes to the game, though, it’s more reminiscent of the Outlast saga, ditching both sanity and Dolores’s elaborate puzzles to speed up progression and get involved in some chases that take little rest. There are still times for exploration and searching for keys or other items – as well as a disturbing new kind of puzzle involving eyes – but the design is more linear and the pacing more intense.

The speed of the character, in fact, rises considerably (which opens a tangent because by default, in the rest of the game, it would not hurt to accelerate the movement a bit more while running). In a gesture that further differentiates this section from the general gameplay, the inventory is emptied (although we do not lose anything, objects in our possession such as pills reappear when we return to the house) and the use of lighters is relieved by a flashlight. unlimited use. Therefore, there is no room for management and backtracking is also reduced, the objective almost always consists of finding the exit in a series of more scripted situations than usual.

This raises an interesting dilemma and is that, on the one hand, Rakan works as a counterpoint to the slower and more methodical terror of Lucy and Dolores, which makes sense when it comes to differentiating them and keeping fresh a development that can rise above ten o’clock. hours if we complete all three chapters (plus the additional exploration we’ll talk about next) at once. But on the other, if evaluated on its own, it can also be seen as the weakest of the three, a step backwards (especially next to Dolores) in terms of design and mechanics that sacrifices the player’s will in pursuit. to create a more dynamic and effective experience.

A possible solution to this, compatible with its anthology status with various influences and game types, would have been to take advantage of that greater break to implement some form of combat. While the paranormal nature of Lucy, Dolores, and other apparitions lend themselves to psychological horror and flight, the hospital introduces a number of more common and abundant enemies that can surround us, also leading to instant deaths and possible moments of frustration. Even denying firearms, it is not difficult to imagine how the simple implementation of commands to cover and strike with some object (even if it only served as momentary rejection) would enrich the playable component while maintaining the lighter pace at which the study was going.

Dwayne: The Beginning and the End

Obviously, we cannot close without commenting on the central quest, sandwiched between the three main chapters, and some general aspects of some importance that apply to the game as a whole. To begin with, completing each chapter provides us, in addition to symbolic objects and the de rigueur achievements, VHS tapes to watch tracks on the living room player (let’s say even the present is not very present). These clues are quite cryptic to begin with, but as we explore and become more familiar with the layout of the house we find so much more tapes as we learn to more clearly identify the locations the videos allude to. From there, it’s time to follow the trail, find new keys or other items, discover inaccessible corners during the other chapters and even participate in some terrifying or hallucinogenic events that put the spotlight on Dwayne.

Given the freedom to undertake it both in terms of order and position in global development — it is easy to make discoveries by accident while trying to solve other tasks — this quest lacks an equally clear thread, but rewards more initiative and ideas. deductive abilities of the player. Some situation may err as obtuse; one in particular, where we must orient ourselves in a dark basement without a lighter, camera or flashlight borders on the chaladura (although if we know it in advance, we can strategically place a candle and alleviate the problem). But some of the best moments derived from exploration arise precisely from this trust in the player to investigate on their own.

Here, too, there are no extra considerations about graphics and control. We already commented before that the sound section is masterful and key both when it comes to instilling terror and guiding us, but the visual also deserves mention for the successful recreation of the house and the dozens and dozens of objects that we can find in it. In some respects, yes, it shows the humility of the project. Certain elements lower the average, clipping makes a frequent appearance when examining things, we can also run into the occasional glitch and character models do not pass the level of scrutiny as well when we see them in detail (returning to PT once more, none have Lisa’s finish).

On the other hand, both the interface and the use of objects can add some unnecessary complications. The game has a double clamping system that allows you to use an object with each hand (for example, carry a lighter on the right and the candle that we want to place on a support on the left, or a bottle with pills to regain sanity) . The idea makes sense, but the execution can be improved, both due to the impossibility of reassigning buttons (at least on consoles) and the need to press several for actions as simple as dropping things, the unintuitive use of inventory to save and retrieve items or the occasional clumsiness of the grip, which emulates with greater or lesser success the physics of the objects (they float in the air as in a virtual reality game and can collide with each other or with the environment). Still, when we’re able to get used to it, Visage delivers what it promises — and more — in terms of horror. Sensitive-hearted players, better abstain.

Grade: 8

CONCLUSION

We are coming to the end of a generation that has seen a much-needed revival for horror in video games. Titles like P.T., Alien Isolation, The Evil Within or even Resident Evil have given it back its good name in the big leagues, while the indie field has continued to flourish thanks to the work of teams like Frictional Games or Red Barrels. SadSquare Studio joins the latter with the intention of evoking the best moments of the former. Visage’s house offers a privileged audiovisual immersion, meaningful exploration, some old-school puzzles and it dares to leave the initial comfort zone to try its luck with different proposals without leaving – or doing it temporarily – its walls. Sometimes it shows the seams of a project with less means than the productions that serve as inspiration, but the final result overcomes it and translates into a long, varied experience and, above all, with an absolutely terrifying atmosphere.

THE BEST

- Masterful setting. Graphics and sound come together to amaze us.

- The house, true protagonist. Huge and full of secrets.

- Even with its possible ups and downs, the conceptual differences between the three chapters make up an interesting and varied offer.

WORST

- The visual finish and the control interface would benefit from certain refinements.

- At some point the progression may be obtuse.