We review the history and operation of a solution against lag with increasing relevance in the competitive scene of fighting games.

As soon as you are interested in fighting games, surely you have read the term rollback netcode more than once. It is far from being a recent invention; in fact, it is a system with more than a decade behind it, but the pandemic and the cancellation of face-to-face fighting events such as EVO have reopened and increased the debate around it. It was precisely one of the founders of this tournament, Tony Cannon, who came up with this solution, designing software to improve the online performance of old games, and since then it has become a new standard for playing classics and classics over the internet. news alike.

A standard, however, with which some companies – particularly in Japan – are still reluctant. Super Smash Bros. Melee, despite being released in 2002 and without online, today offers a more efficient netcode than Ultimate, delivered in 2018 with a payment service provided by Nintendo. And Dragon Ball FighterZ, one of the star names in the current competitive scene, has suffered more in 2020 than games like Killer Instinct or Mortal Kombat 11 due to its permanence in the old system, known as delay-based netcode. It is something that, luckily, Arc System Works will remedy in Guilty Gear Strive, a game whose beta has served to remind us why rollback is the way to go. So today we will walk back, to the beginning of that path, to see how it was drawn in the first place.

Once upon a time … the online fight

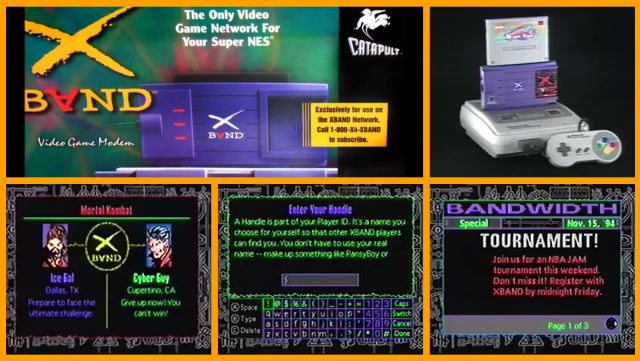

It all started in Cupertino, California. Well, you could say that it started in many places. In the universities where both the first primitive video games and the first online infrastructures were created. At the studios’ offices they tried their hand at fighting from countless perspectives before Street Fighter II redefined the genre. Or, of course, at Capcom’s own headquarters, which thirty years ago launched one of the most essential works in the medium. But for the sake of brevity, we’ll skip all of that and jump straight to 1994, when a much lesser-known company, Catapult Entertainment, created a peripheral called XBAND.

Distributed by THQ and sold on the Blockbuster chain of video stores, XBAND was a modem that allowed to play online on Mega Drive and SNES. The artifact got the go-ahead from Sega and Nintendo, although its authors had to implement the compatibility on their own, using reverse engineering to enable it in a selection of games that included Super Mario Kart, Killer Instinct, Mortal Kombat 3, the sports titles of EA (Madden, NBA Live, NHL) and, of course, Super Street Fighter II. It was a first attempt with fairly moderate success and practically limited to the United States – it did not reach Europe and its presence in Japan was anecdotal – but functional and with features such as skill level matching, download of leaderboards, text chat and the occasional holding of national tournaments.

Although it was not the beginning of online gaming as such, XBAND did show both its potential and the possible limitations on consoles. Using the phone line, the program written by Catapult linked the modems of two players and made their games believe that the controllers were connected to the same console. A surprisingly viable technological feat, but challenged by the need to record the pressing of the buttons on one remote control and the other and exchange that information between the two houses before displaying its effects on the screen. This process of waiting for the transfer and execution of each maneuver is what we know as network delay and, in an ideal scenario, it is carried out in such a short period that it is practically imperceptible to the player.

However, ideal cases do not have to be the norm, not now or between 1994 and 1997 (XBAND’s active period). The connection speed was sufficient to transmit instructions as simple as those required by Street Fighter II, but, as the versed will know, the time required to transmit data depends on latency (or ping, measured in milliseconds), and that factor was more variable according to area and distance, sometimes creating significant delays in the processing of actions (network lag). The simplest palliative was to try to connect with players as close as possible, although the designers of WeaponLord (a SNES and Mega Drive game created with XBAND already in mind) also tried to counter it with a combat based more on complexity than speed and a system de parries with weapons that made it easier to defend against cross-ups in laggy situations.

New millennium, new opportunity

Despite the viability demonstrated by a third party company in 16-bit consoles, it took two more generations to see a full commitment to the service. Catapult would implement XBAND on Saturn, which offered its own first party modem (Sega Net Link), and Nintendo also had its forays into Japan through the failed 64DD peripheral, but it was Dreamcast that ushered in a new era of online on consoles on a global scale. Some probably remember the arrival of ChuChu Rocket! to Europe in the summer of 2000, symbolic launch, but just a prelude to what it would be like to play Phantasy Star Online or Quake III: Arena. Or Halo 2 when Microsoft picked up the baton from Sega with its Xbox Live. Infrastructures improved and approached a level that computers had offered for years.

However, fighting games still posed their own challenges. Yes, the connections were faster and allowed more players to connect at the same time, in games with increasingly complex operations. But in the 1v1 of the fight, where victories were decided in tenths of a second, latency was still the key factor and, at the same time, the most fallible. Emblematic titles of the time such as Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike or Soul Calibur I, II and III (pseudo successors of WeaponLord and its combat with weapons and parries) went on sale without online. It was a genre still geared towards arcades, local games, and face-to-face tournaments (like EVO), doomed to the niche category as the internet became a more and more important multiplayer presence.

Good Game, Peace Out

In August 2006, months before the arrival of the Wii and PlayStation 3, Capcom relaunched Street Fighter II: Hyper Fighting on the Xbox 360 digital store and became the best-seller on the platform during its first 24 hours. A success, yes, soon overshadowed by complaints about lag, present both among the press and among users. As in the long-ago days of XBAND, delay-based netcode only offered a completely smooth gaming experience if the latency was low enough to exchange the information of the two players and draw the synchronized result in less than a period of time. 50 milliseconds (or 3 frames of a game that runs at 60 fps), something that neither in 2006, nor now in 2021, can be guaranteed.

An important idea, before going any further, is that lag as such will always exist. A ping of 0 milliseconds is impractical because, even in an ideal scenario, the signal must travel a physical distance and undergo identification protocols along the way. From there, factors such as a good netcode, the proximity between players or the use of Ethernet cable contribute to its reduction, while a congested netcode and the loss of information packets contribute to its increase. But neither the best of the connections serves to achieve the absence of lag, the total consistency in the transmission rate nor, of course, that the player on the other side does not weigh down the experience if he suffers his own fluctuations in the line.

This is where we return to Cupertino and Tony Cannon – unrelated to Catapult Entertainment, but hailing from the same city. Seeing the problems plaguing Street Fighter II on its Xbox 360 relaunch, the EVO co-founder became frustrated by Capcom’s inability to revive in a declining genre and set to work on his own solution. The result was the rollback netcode, a system that can be implemented through a program called GGPO (Good Game, Peace Out) that, naturally, did not reduce latency – something outside the possibilities of the game – but did mitigate its effects by replacing the wait with a prediction which was later corrected – if necessary – when the information arrived from the other end.

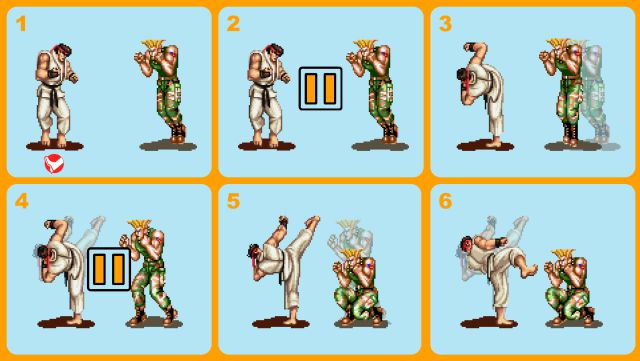

So that it doesn’t sound abstract, let’s do a little role-play with an example of each method. In the initial box of the image below these lines, based on the delay-based netcode method, the player controlling Ryu presses an attack button. Playing offline, the action would be reflected in the next frame, but playing online, the transit of information stops the action (an imperceptible or perceptible amount of time depending on the latency) to synchronize and start executing the attack after registering Guile’s new position . The same operation is then repeated in box 4, when the game again checks the position of the other player.

If the latency is low, this exchange takes place in a few milliseconds and the player does not perceive any pauses. If the latency is high, the number of frames required for correct synchronization increases – the framerate not only updates the visual representation, but also the underlying playable logic – which can lead to clear stops and even a practically unplayable game in cases more extreme.

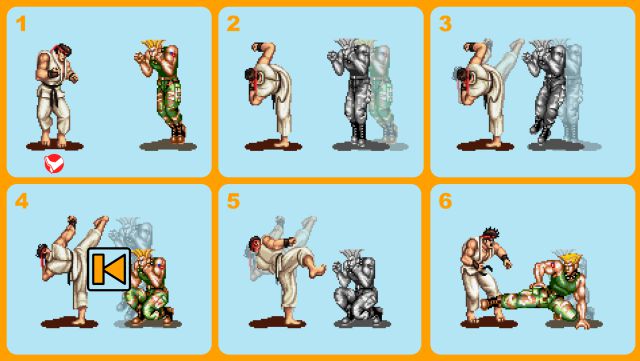

Now let’s look at the same situation using rollback netcode: after pressing the attack button, the animation starts running instantly because the game is in charge of momentarily simulating Guile’s actions (illustrated below using black and white). Once the information of the other player appears, if said simulation coincides with what has happened on the other side (again, we are talking about thousandths of a second), the game continues its course as if it had not interceded. If there is disparity – like the one we created below by giving an example with notable lag – it backs up (hence the term rollback) and immediately shows the correct location of the other player.

It goes without saying that if the latency is very high, this kind of “teleportation” can also become a serious problem, preventing the correct course of the games. It’s a clever trick, not magic. But within common margins, or even more restrictive, rollback makes the game experience more fluid and precise than delay-based, since the inputs of both players are always registered and executed instantly – something that does not happen. on the delayed system.

Hybridization and expansion

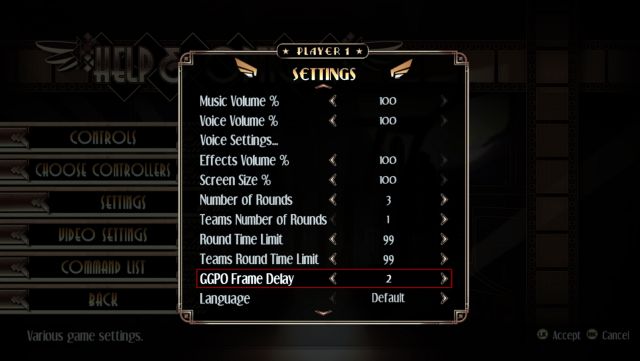

Another key aspect of rollback is that it is not just an alternative, but also an add-on. Both systems can coexist in the same game so, as soon as the GGPO solution began to gain traction both in the emulation landscape and among the developers of official ports (such as Super Street Fighter II Turbo HD Remix or Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike Online) and even new games (like Skullgirls), a hybridization soon took place: Killer Instinct and Injustice 2, for example, set 3 maximum frames of delay, at which point the rollback goes into effect to prevent the action from stop; while others, such as Darkstalkers Resurrection or the aforementioned Skullgirls, have chosen to implement selectors so that players choose their own balance between systems.

So if it brings such clear benefits and doesn’t override the other method, why is rollback still missing in high-profile games almost 15 years after GGPO’s release? A recurring factor, which we already dropped at the beginning, is the greater reluctance of Japanese developers to incorporate technology created outside. Western sagas such as Injustice or Mortal Kombat jumped quickly to the new wagon, and modern Capcom ports such as Street Fighter or Darkstalkers were carried out by Iron Galaxy, an American studio also responsible for the last seasons of Killer Instinct, but in Japanese lands they have preferred to continue working with their methods, familiar and functional in connections within the country. Now, luckily, the turn towards the rollback begins to materialize in promises like those of Guilty Gear Strive or King of Fighters XV, although it is still an acclimatization in process.

Of course, introducing rollback is not just a matter of opening up to other technologies, but also of preparing new infrastructures and optimizing – or creating from scratch – other types of operations. Getting the game to take control of a character in Dragon Ball FighterZ, simulate their forward behavior, store the intermediate states and revert to any of them or a new one instantly is a much more complicated task than in Street Fighter II. In essence, it requires processing theoretical scenarios that are not shown on the screen, and that may never be shown, but that consume computational power anyway.

Efficient engineering work may allow a solution to be patched one of these days (Mortal Kombat X did it quite a few months after its release), but the ideal, of course, is to build the games with rollback netcode in mind from scratch. So even if some of these present opportunities are lost, if the industry keeps pushing to make it a requirement of online competition, it will surely end up being so sooner or later.