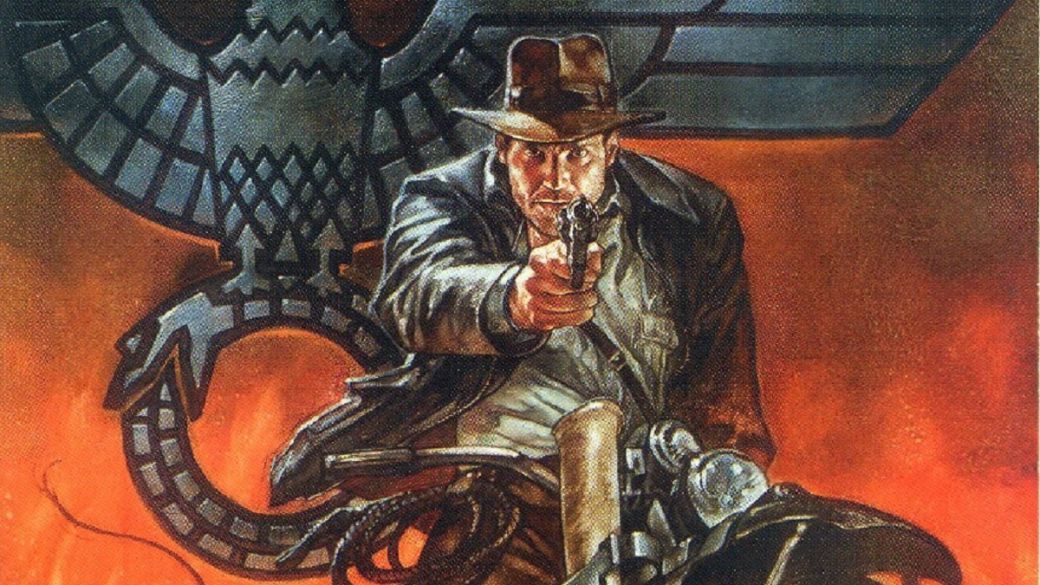

We review what could have been the third Indiana Jones graphic adventure after The Last Crusade and Fate of Atlantis

Now that Indiana Jones is making a big splash in the video game world thanks to Bethesda’s announcement that it is working on a new title from the archaeologist by MachineGames, it is a great time to look back at what could have been one of the best Indy games, composing a trilogy with the unforgettable graphic adventures of The Last Crusade and Fate of Atlantis: the canceled SCUMM adventure called Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix.

Creating a new adventure

Around 1993, given the good results with Fate of Atlantis, the idea of doing a new adventure game with the archaeologist was pretty clear. A small group was formed to conceive the general concept; Hal Barwood, the development lead for Fate of Atlantis, chose to step aside to focus on other projects and stayed as a “consultant.” In his place came as co-development leaders Joe Pinney (who we have become better known thanks to his extensive work at Telltale) and William Stoneham, sharing the design and art directions between them respectively. Anson Jew, who had worked on the animations for Fate of Atlantis (and who has also participated as an artist and animator in productions such as Full Throttle, The Curse of Monkey Island or Herc’s Adventures), would finish composing the hard core from which the draft.

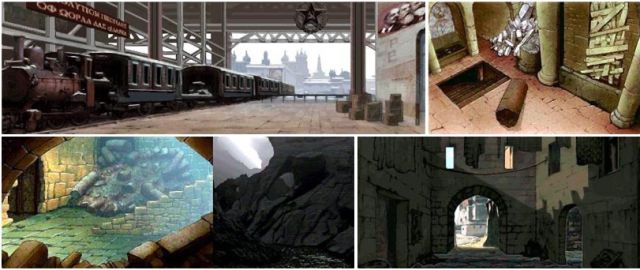

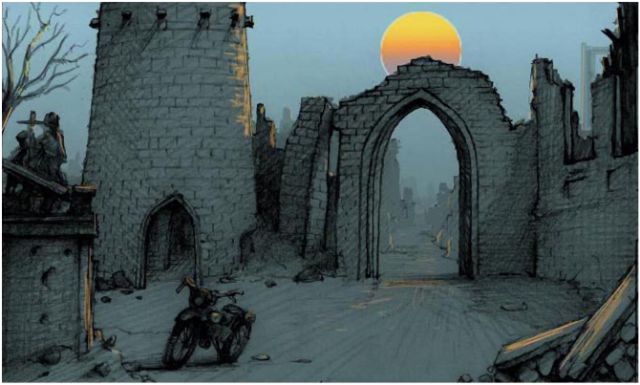

Wallpapers created by William “Bill” Stoneham

The general idea was to focus the action in 1947, with a more mature Indy and the Third Reich defeated but kicking through the surviving Nazi officers who escaped the Nuremberg trials, many of them to South America. The plot would revolve around a mythical object: the philosopher’s stone, an object whose possession could resurrect Hitler himself and provide an emerging new Reich with enough uranium to launch a surprise nuclear attack against allied enemies that would defeat them before being able to react. . Along with Indiana, a Russian cazanazis named Nadia Kirov, would play the role of co-protagonist, repeating the play of the dynamic of two protagonists that was already used in Fate of Atlantis with Sophia; with the background of the beginning of the cold war and the growing distrust between Russia and the USA to specialize the relationship. The name “Iron Phoenix” was in reference to the main argument of the restoration of the reich and the desire to resurrect the Führer.

In theory it should have been a clear project. SCUMM was more than dominated and there was no hint of wanting to go on adventures when it came to the engine as happened to The Dig; the team also had experience and several members of Fate of Atlantis were involved in the project. While no development is easy, it should have been something quite affordable for LucasArts at the time, but a series of misfortunes fell on the game.

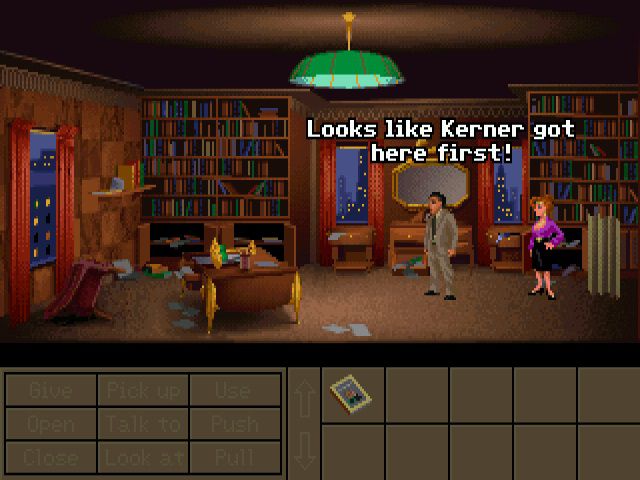

Fate of Atlantis was the base, but you had to go further

Difficulties from the beginning

The first and earliest was the departure of Pinney, one of the co-leaders, due to unclear circumstances and without a clear replacement to fill his position. Ron Gilbert was no longer in Lucas, Dave Grossman went with him, and Tim Schafer was with an unknown project (which was not Full Throttle). Finally it would be Aric Wilmunder who would take his place, being one of the veterans of the study and a fundamental figure in the golden age of LucasArts as the engineer in charge of maintaining and improving the SCUMM system devised by Gilbert and Morningstar (suffice it to say that his nickname in the studio was “SCUMM Lord”). After three intense months of collaborative work on the scaffolding left by Penney, he produced an extensive 60-page document detailing everything that would have been this adventure, including development and all kinds of details argumentative and descriptive that should have been the bible that guided the development team to the achievement of the goal (this document has been fortunately preserved thanks to the fantastic work of preserving the history of SCUMM that Wilmunder himself has done and is a must read for anyone who aspires to know more about the role of a video game designer ”).

It seemed all on rails again, but new clouds loomed as the production phase was about to begin. On the one hand, Aric was a highly demanded figure at LucasArts (his constant presence in the credits of all the games from the studio’s golden age proves this). In theory, the presence of other engineers skilled in handling SCUMM is what should have allowed him to focus on his role as director of design and co-development leader of the Indiana Jones game, but the stormy development of The Dig in his third attempt since 1989 (six years of development, an outrage at the time) continued to charge sacrifices. The creators of Sam & Max, Sean Clark and Mike Stemmle, were convinced / forced to take over the controls of The Dig with the mission of finishing it and launching it on the market yes or yes, but among the conditions they put in order to do so was that of have Wilmunder’s full support, forcing him to divide and prioritize.

Day of the Tentacle forced the visual bar for characters to rise

Problems also arose in the art department. The launch of Day of the Tentacle had raised the visual bar and the board demanded that the team’s new games match the graphic impact of the Maniac Mansion sequel, which necessarily went through larger and more detailed characters. Bill Stoneham began to create detailed backdrops of the exotic locations Indy would visit on his new adventure around the world, but when creating the character, animator Anson Jew found it necessary to pose and animate an Indiana Jones of realistic proportions and two times bigger than in previous games, it necessarily had to have more color palettes, a shared resource with the funds themselves given the technology of the time. This proved to be a challenge and a source of conflict between departments that in Day of the Tentacle had been saved thanks to the cartoon design and the comical proportions of the characters, suitable for a comedy but not for a game like this. Nothing insurmountable, but one more problem to add to the list.

Mindless outsourcing

However, the death of Iron Phoenix was signed when an attempt was made to outsource part of the development to a Canadian study, a purely economic move resulting from non-existent leadership due to the incessant carousel of LucasArts presidents who came and went every two years, some with a questionable knowledge of the video game market. Specifically, the idea was to outsource the bulk of development to a team that had never created adventure games, with the promise that Canadian tax breaks and financial aid would pay for the project. Of course it was a disaster, it was not only that the telematics possibilities of 1994 were not the ones of today, it is that the contracted team was unable to produce what was requested by many trips to Montreal that Bill and Wilmunder did. It was like asking a youth baseball team to compete in the NBA; nor did they have the knowledge or skill level to produce something that would be worth the experienced LucasArts teams back then.

Wilmunder, tired and disillusioned, with a job going nowhere, decided to fully focus on the other development nightmare that was The Dig, a game that came straight from George Lucas and was branded by Steven Spielberg, so there was pressure to get it out anyway. Of course, the outsourcing invention ended in failure and LucasArts cut the contract; both circumstances left the Iron Phoenix with few defenders in the dome, although Wilmunder still hoped that the remaining team could work through the design. However, there was one last point: Germany, the main market for LucasArts’ adventure games by far from the USA, had severe laws against the use of Nazi symbols that affected any product, with few exceptions for films and certain cultural content that of course, it did not extend to video games. Until that moment it had been avoided by modifying the German version of the Indiana Jones games to change the iconography and eliminate references in the dialogue; but Iron Phoenix was a game in which the antagonist’s goal was to resurrect Adolf Hitler, graphic representation included. There was no edition that could get around that and the German distributor guaranteed them that they couldn’t sell it there on such an argument. There he lost all the air he had left and the project ceased to exist at some point between 94 and 95 without much ceremony on the part of the board.

The ashes of the Iron Phoenix

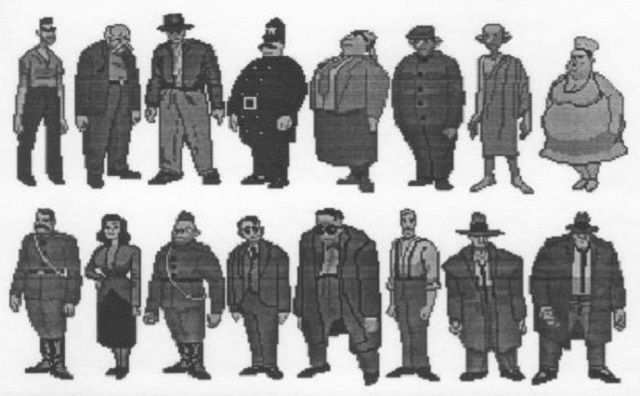

Given that production never really started due to the lack of real resources and the inoperation of the hired Canadian studio, there aren’t many vestiges of the game left to hold on to. The most solid thing is Wilmunder’s design document that shows us what it would have been: puzzles, locations, situations and general plot from start to finish, with a structure based on the “three ways” that had been developed successfully in Fate of Atlantis and some technical innovations resulting from the evolution of SCUMM. The arts department experimented with more use of rotoscopic animations and some daring fusion experiments with interactive real video – the results of which would later crystallize in Rebel Assault II. There are also various sketches, background art and a small fragment of a varied video of animations made by Anson Jew shows us the animation sequence in which, we imagine, the attempt to resurrect Hitler was aborted. As (very poor) consolation prize is the comic book miniseries Fate of Atlantis, an agreement with Dark Horse to use the ideas of what the video game was going to be, but which in the end is a poor version of the original script, devoid of many details, with questionable creative licenses on the characters and with an ending that has nothing to do with it.

Another of the few conceptual designs that has been preserved

It would be the last time we would see an attempt at a graphic adventure with Indiana Jones and a missed opportunity to enjoy a title at the height of Fate of Atlantis. Despite being his most prestigious and valued games, the sales of Lucas’s graphic adventures were not particularly remarkable and later Indiana Jones games would go on the side of 3D action and adventure such as The Emperor’s Tomb or Infernal Machine. At least the preserved documentation allows us to fantasize about what it might have been. And while we are certain that the Bethesda game will not be a graphic adventure, perhaps the resurrected LucasArts label has some surprises in store for us for the future from some of the talented studios capable of creating graphic adventures today. Dreaming is free.

Sources:

- Original paper by Aric Wilmunder

- Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix: The Lost Sequel to Fate of Atlantis